|

|

|

|

| |

Editorial Editorial |

|

The identification of the Range of

Circumstances in the Participating Countries has been the main

outcome of

the analysis phase in the WaterStrategyMan Project.

In order to determine the

issues faced in managing water resources in arid and semi-arid

regions, a detailed definition was sought of the current conditions in water

deficient regions in terms of water resources, water supply, use

patterns, water management practices and policies.

The project partners, therefore, determined those conditions in the

designated countries, and

through these reviews selected regions facing water scarcity for

further study.

Fifteen regions were

eventually selected as candidates for case study, and were further analyzed with respect to their specific

characteristics. Of those, six were the ones finally picked as

representative case studies, after a comprehensive typology analysis

according to the identified water related problems.

This issue of the WSM Newsletter

showcases the Range of Circumstances in Greece and in the three Greek candidate regions, Attica,

Thessaly and the Cyclades Islands. This editorial is

followed by a summary overview of the country, while the detailed texts can

be found by clicking the links under "Topics" in the left

bar.

The following Newsletter issues will

present the wide range of

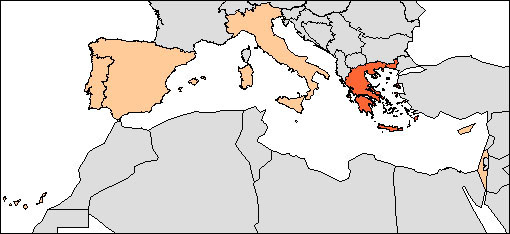

circumstances in the other five countries (Italy,

Spain, Portugal, Cyprus and Israel) and an overview of the

candidate regions.

|

|

|

The

WaterStrategyMan

Project (Developing Strategies for Regulating and Managing Water Resources

and Demand in Water Deficient Regions / WSM), is supported

by the European Commission under the Fifth Framework

Programme, under the Key Action "Sustainable Management

and Quality of Water".

|

|

Overview of Greece

Overview of Greece |

Introduction |

|

Greece has

one of the greatest water resources potentials per capita in the

Mediterranean area, and theoretically should have ample water for

its population and traditional water uses; however water is not

evenly distributed in space and time.

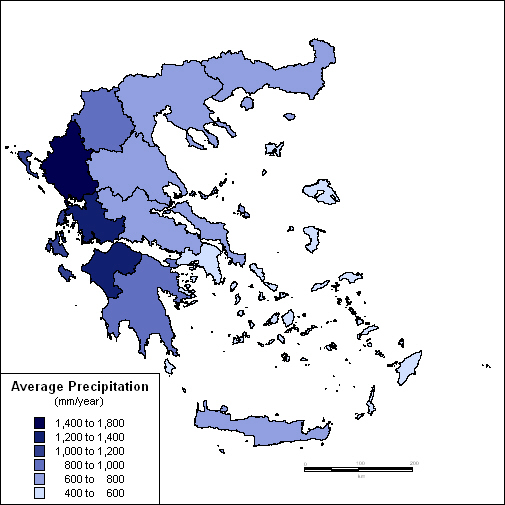

The maximum

precipitation is recorded in the western parts, where the available

water resources are consequently plentiful, while in other regions

of the country precipitation is much lower and available water

resources are insufficient to meet a growing demand.

Due to this

inequality in water distribution, both in space and time, some areas

of Greece, such as Attica and the Aegean Islands are facing

long-term water shortage problems.

The permanent population of Greece according to

the 2001 census was 10,964,080 inhabitants. The recorded tourist

arrivals for 1998 were 11,363,822.

|

The climate in general is

Mediterranean but varies significantly throughout the country due to

various factors (the country being almost surrounded by

sea, its geomorphology, and the north – south direction of the main

mountainous chain).

In the country there are no plains in the geographical sense

but only basins formed between mountain chains. One of the main

characteristics of the country is its extended coastline and the

significant number of islands. Geological formations are mainly composed of limestone and

sedimentary rocks.

Figure 1 presents

the geomorphology of the country, and Figure 3 shows the average precipitation

per administrative region. These are 13 in total, and their

boundaries do not

entirely coincide with the 14 water regions (hydrological

departments).

|

|

|

|

Figure 1. Geomorphology of Greece

|

|

|

Water Demand and Supply

Status |

|

Water demand peaks in the

hot and dry summer months, when water availability is at its lowest,

due to the decrease in precipitation. The summer peak is due to the

heat that encourages increased water usage, to the tourist

activities and to the

current irrigation practices and cultivated crop types.

In addition to the limited water resources, water pressure

in some parts of the country may also be attributed to the large influx of visitors from other

parts of the country or from abroad. Figures for tourist numbers

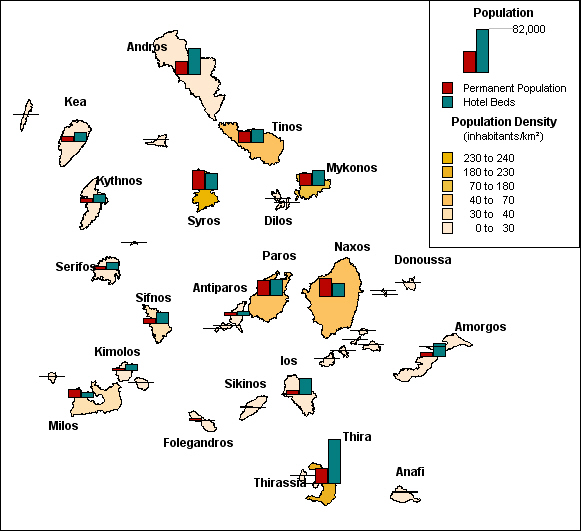

vary from year to year and between measurements. The Aegean Islands have the

highest visitor/tourist number compared to the permanent population.

For example, in August the peak number of visitors to the Aegean Islands is on

the average ten times greater than the local population, and in

certain islands it is even thirty times the local one (Figure 2).

|

Approximately 14 km3/y of

water entering Greece (about 30% of total average annual water

resources) originates in neighbouring nations, where the water is

both abstracted and used for effluent disposal.

The estimated

amount of stored groundwater is about 10,300 hm3/year,

formed primarily in sedimentary materials.

Nearly 100% of the Greek population is

connected to water supply and power utilities, while 76% of the

population is connected to sewerage and wastewater treatment

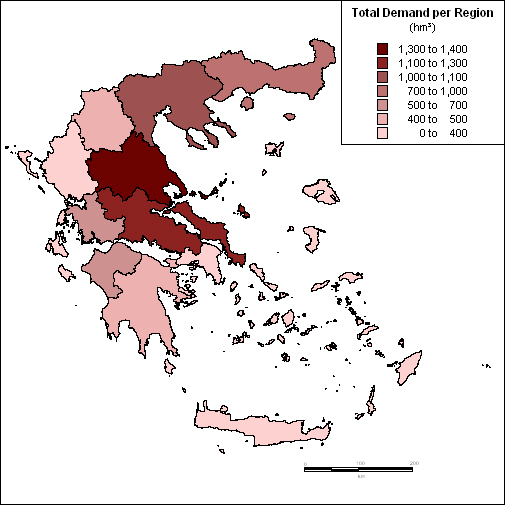

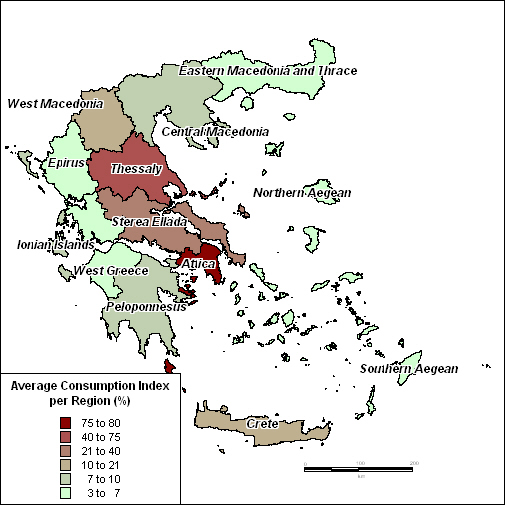

networks. Figure 4 presents

the water demand per region, while Figure 5 shows the Consumption

Index per Region. The Consumption index is the ratio of water

consumed over the total water resources, expressed as a percentage. |

|

|

Figure 2. Population density

vs. accommodation availability

in the Cycladic Islands (1996) |

|

Conflicts arise in cases that the rivers are overabstracted upstream, and

where the quality of the waters deteriorates to the point that it

cannot be used for its intended use downstream. Since international

agreements are still pending and the rate of exploitation increases

in the upstream countries, quantity conflicts are also due to

happen.

- In areas dependent on tourism,

as the domestic

supply takes priority over irrigation, conflicts invariably arise

between the municipal water supply and the local farmers. The available water

resources in the Greek islands are very limited, and with few

exceptions consist of groundwater contained in the local aquifers.

Overabstraction of those aquifers leads to salinisation of

the water rendering it mostly unusable. The soils in the islands

are extremely vulnerable to erosion with resulting problems in

developing the water resources.

|

- In agricultural areas conflict arises due to the excessive

demand for irrigation water, while large quantities are required

for domestic supply, tourist activities and for maintaining the

ecological characteristics of the surface and ground water of the

area. The agricultural activities and practices in Greece have

neither been “modernised” nor adapted to current requirements and

standards, leading to vast amounts of water used for irrigation

(85% of all demand), that could be drastically reduced through the

introduction of more efficient irrigation networks and a better

selection of crops in terms of water needs.

- In urban centers the main area for conflict is the transfer

of water from other, richer in water resources regions, or the

exploitation of water resources that would be used for irrigation.

The Metropolitan Athens Area and Thessalonica are both water

deficient urban centres.

|

|

|

Figure 3. Average precipitation

in the 13 administrative regions

|

|

|

Environment and

protection |

|

Coastal waters

of Greece are of good quality, with the exception of areas where

effluents from the larger cities are

discharged. The same does not apply to the surface and

ground waters. Domestic effluents and

agrochemicals are a major source of surface and groundwater

pollution, despite the existing EU legislation for wastewater

treatment. Until now, water pollution has been one of the main

issues in trans-boundary water resources, as the disposal of raw

domestic and industrial effluents has had profound effects on rivers.

No effluent charging systems exist and the sewage is discharged into

the wastewater system for a nominal charge.

|

The quality of Greek river systems is

dependent on the time of the year; water levels decrease

significantly in the summer allowing higher concentrations of

pollutants. Overabstraction and saline

intrusion in the underground aquifers exacerbates the problem of

groundwater deterioration and increases the water shortage problems.

Another important issue is the occurrence of periodic droughts and floods in increasing frequency in the recent years. The combination of prolonged drought periods with intermittent

floods after torrential rainfall worsens the pollution problems

of urban and agricultural runoff.

|

|

|

Figure 4. Water Demand in the

13 administrative regions

|

|

|

Institutional framework and constraints |

|

The administration and management of water is

at the moment undergoing major changes due to the process of Greek

legislation harmonization with respect to the European Water

Framework Directive. At present, new legislation has been announced

but not yet submitted for approval to the Parliament. Therefore the

description of the institutional framework and

management of water resources in the following paragraphs refers to the current situation

and does not reflect the

Water Framework Directive values and principles.

Responsibility on water

allocation and management is distributed in the national, regional

and local levels of administration. The initial allocation of water

is effected by the Ministry of Development, which is responsible for

water allocation to individual uses, as well as for the management

of water designated for industrial use. Once the initial allocation

is effected, the water for each use falls under the responsibility

of the respective ministry.

On the regional level, the

regional authorities are responsible for the approval of planning

and financing for projects involving water supply and irrigation.

|

Prefecture authorities are responsible for the issuing of permits

for abstraction and for the allocation of water within each

region/use. On the local/municipal level, the municipality is

responsible for the supply water and services to the people, or, for

the creation of public companies responsible for the provision of

water and sanitary services.

The most pressing issue is

the fact that there are many government departments dealing with

water problems, but their activities are compartmentalized and not

well coordinated.

Added to this is a water law system which is not

responsive to integrated water resources management and widely

scattered, thus permitting overlapping functions, multiple advisory

bodies and insufficiently decentralized management responsibilities

through regional organizations. Legislation also tends to be deficient in the

case of pollution issues, where quality standards for water bodies

and/or effluent disposal have not been clearly established.

A Master Plan has yet to be

formulated along with the corresponding management principles for

the 14 water regions.

|

|

|

Figure 5. Consumption Index

in the 13 administrative regions

|

|

|

Management, Institutional and policy options |

|

The Greek legal system includes several laws and regulations for the allocation of water

resources, the management of water resources and services, and the

quality and quantity aspects of water regarding each use. According

to Article 24 of the Greek Constitution, the protection of the

natural environment is a responsibility not only of the state but

also of the citizens. The state is under obligation to take

preventive and corrective measures for the protection of the natural

environment, both on the legislative and the administrative level. The protection of water

resources is also regulated by a number of international agreements

and legislation.

Currently the focus in

Greece is on growth policies rather than on water resources

management and policies. Law 1739/1987 (which as mentioned above is

under revision) provides the basic framework

for water management, which is however not currently fully applied.

The management of resources is essentially effected on a regional

level, after the initial allocation to uses.

The management of water resources is

often poor and

disorganized in the municipal level. Maintenance of infrastructure in the more remote areas

tends to be poor, while long term contingency planning is almost

non-existent. Financial constraints are the main reason behind the

poor management and lack of planning.

Figure 6 presents the decision making process in Greece as it currently stands.

|

Overall short-term responses

to water challenges are driven by crises that require the

confrontation of the acute shortages. In cases of water shortage,

supply augmentation management options are used most often.

Demand reduction management principles have

been used in the past, particularly in the Athens Metropolitan Area

in the early 1990’s, where increased water prices were successfully

used to compensate for the prolonged drought that led to severe

water shortages. However, such measures are not widely used as the price of water tends

to play a pivotal role in political processes.

The means used to

confront water shortages have depended mainly on the cost of the

method; the first response to water shortages invariably

involves new drilling of the aquifers. An alternative way

of ensuring water supply is importing water from neighbouring,

richer in water areas, and for permanent water shortage other structural solutions are

preferred - dams and reservoirs are used where there are funds

available, and locations suitable, for their construction. Desalination plants are also used in cases of more

limited funds or lack of suitable locations.

There is great need for new

approaches to water management that will mitigate such problem issues and constraints, and promote

sustainable use of the available resources. A strategic approach is

required

that should include drastic measures of ecological rehabilitation,

innovative institutional mechanisms, and a balance between autonomy

and cooperation.

|

|

|

Figure 6. The current decision making

process

|

|

|

Summary of water-related issues in

Greece |

- Dependence on transboundary waters flowing from non-EU regions,

which are very difficult to regulate,

particularly in matters of quality; the lack of infrastructure

in the neighboring countries results in pollution downstream into

Greek waters.

- Strong dependence on irrigation. Even with the best management

techniques and strategies, agriculture will remain the major user

of water in the country, due to the hot and dry climate.

- Pronounced seasonality of demand, which makes the provision

of water services harder, as it is not always possible to ensure

adequate supply.

i) The demand that is due to tourism peaks in the summer when a major influx of tourists is

observed.

ii) The demand for agriculture peaks in the

dry hot season, the same time as the domestic demand peaks due to

tourism.

- Uneven distribution of resources. Both precipitation and surface water resources are concentrated in the

western and northern parts of the country that are self-sufficient,

while the eastern and southern parts of the country face water

shortages.

- Water quality deterioration due to human activities.

|

- Uneven distribution of population and hyperurbanization. The population is

largely concentrated in the eastern coastal areas which

tend to be under stress. Furthermore, the concentration of almost

half the Greek population in Athens, in the poorest water region

of the country, and the seasonal influx of visitors to the Greek

islands, exacerbates the water shortage problems.

- Overexploitation and salinisation of aquifers, which is a common

problem in the areas dependent on groundwater, and particularly

in coastal areas.

- Focus on short–term developmental policies rather on the

actual water resource management.

- Lack of inter-ministerial coordination and overlaps in areas

of authority. Instead of an organized, coordinated approach to

water resources management, measures taken are only partial and

generally ineffective.

- Absence of master plans or national guidelines for comprehensive

planning and management in the past, despite recent efforts for

responding to that problem.

- Lack of organized, collective efforts, which are required to

respond to the demanding provisions of the Water Framework Directive

and other EU legislation and operational guidelines.

|

|

|

|

|