Spain

Abstract

Although Spain's water resources related to population, in global terms,

are actually above the Mediterranean, water in Spain can be considered a scarce

resource and extremely vulnerable. This is caused by its unequal spatial

distribution, with excedentary basins and extremely deficitary basins, and by factors such as population growth

and displacement, tourist growth in coastal areas or continuous increase of

irrigation in arid and semiarid areas, which are clearly deficitary.

Competency and management overlapping regarding resource use and re-use,

seriously threaten the policies on water sustainable use that try to start both

at the national and Autonomous Region level. The great biodiversity and water

environment richness is also threatened due to the big local and regional

disarrangement as regards the assignment of water resources.

Among the

different hydrographic regions and deficitary basins, the two cases of the

Canary Islands and of Doñana

and its surroundings have been selected. The Canary Islands show a complete range of risks and

conflict situations within a deficitary territory

with a spectacular tourist growth. Doñana

represents the paradigm of conservation and development, an environment where

population pressure and water table exploitation for new crops has to

conciliate with the conservation of one of the most important wetlands in the

world. The range of circumstances in these two regions is analysed, and

presented in table form.

Introduction

We can say concisely that

there is a strong difference between Northern and North-western areas with

abundant water resources and the dry Southern and Eastern areas. Schematically,

three large sectors can be differentiated, with regard to abundance and

distribution of water resources:

Northern and North-western

sector, including

The Central sector,

constituted by the large inner river basins, shows the pluviometric

shadow by the surrounding mountain systems, receiving little rainfall, with an rise in aridity in the most continental areas (middle

The Mediterranean sector is

constituted by small river basins and average slopes towards the sea. Pluviometry is generally quit low, due to its localisation

in a sector of shadow with regard to the humid North-western winds. To be

emphasised the marked irregularity of precipitations with long drought periods

and catastrophic episodes of convective rainfalls. Scarcity and irregularity is

not compensated by rivers’ contribution, as river basins are quite small in

this sector and with a torrent regime, lacking big water-producers orographic centres. Natural scarcity of water increases

going southwards, reaching its maximum levels in the coastal areas of

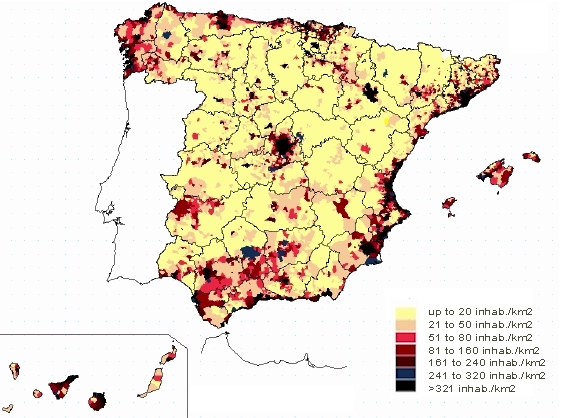

The permanent population of

Map 1.

Table 1. Summary of

|

Background |

Description |

|

Climate |

The main characteristic of The Northern part is

characterised by a mild climate, with storms of Atlantic origin that are

practically present all the year round, giving rise to a high relative

humidity and mild temperatures, temperate in winter and cool in summer. In

the Mediterranean coast and part of inner Climate is generally dry in the Canary Islands

(especially in the eastern islands, as the western ones are influenced by

Atlantic air masses charged with humidity) and in the coastal area of Murcia

and Almeria, where only scarce precipitations

occur. In accordance with the humidity UNESCO’s Global Humidity

Index, based on a ratio of annual precipitation and potential evapo-transpiration (P/PET) index, ·

Arid areas: Eastern mainland sector,

eastern-southern areas of the ·

Semi-arid areas: ·

Sub-humid: ·

Humid: |

|

Geology |

One of the most relevant

features of Spanish mainland is its central plateau, flat lands with average

altitude of 600 m above the sea level that occupy nearly half of the Spanish

area. It is vertebrated by the Central Cordillera,

characterised by granitic and shale formations. The

origin of the plateau lies in the existence of two depressions of the

basement that were filled by hundreds of metres of clay-loamy and gypsiferous sediments coming from the adjacent mountain

chains. There are other two outstanding deep depressions ( |

|

Geomorphology |

|

|

Soils |

According with the Soil

Taxonomy classification, in |

|

Surface water |

The little river

flow reveals the scarce pluviometry within the

hydrographical network. Big collectors are divided in those coming from the

central plateau ( In |

|

Water storage features |

Dam capacity is at present

of 53,191 hm3 (INE 2001). This quantity is one of the highest dam

index ratio in A good percentage of these is

constituted by dams with hydroelectric capacity: Maximum capacity of

hydroelectric dams is 18,047 million kWh (UNESA, 1997). |

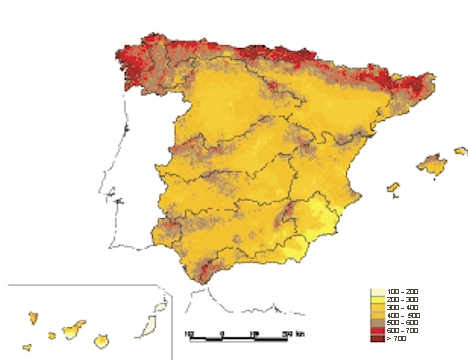

Map 2: Climatic

classification according with the UNESCO’s humidity index

Map 3.: Precipitations

in

Map 4.:Actual yearly average evapo-transpiration

Overview

of the country

Water Demand and Supply Status

Urban water supply

This demand encloses the one

originated in population centres, both to satisfy domestic consumption and

linked to other activities, can be industrial or service-related. It sums up to

some 4,700 hm3 /year.

Coastal concentration of population specially affect

the Mediterranean area, with in a process tending to coastal conurbation. The

important tourist development of these regions, which in many cases is the main

economic activity, sums to this demographic distribution feature and water

spatial demand. Tourist activities produce an approximate yearly increase of

10% in the population demand, although the increase is higher due to the high

consumption of several recreational activities. This increase is very

concentrated in time, more precisely in the summer period, which have bigger supply problems.

Forecasts made by the basin hydrological plans suggest increases of 15%

and 36% on the present situation, in 10 and 20 years respectively. The

draught periods of the last decade have shown the serious risks of lack of

supply in large regions.

As regards sewerage, the percentage of purified urban waste water is

around 60%, although only 45% meets the requirements of Directive 91/271.

Industry

Yearly water quantity dedicated to industry use in

Irrigation

Quantitatively speaking, irrigation is the main use of water in

Environmental requirements

Conservation of ecological and

landscape resources linked with water requires maintaining minimum flows: water

table discharges, river flow-level or quantity of water reaching the sea at the

river mouth, without which these resources can suffer a strong degradation. In

the Mediterranean area and in the south there is a clear concentration of the

risk of scarcity, and this situation corresponds to the natural scarce

availability of water resources and to the high concentration of demands that

concern all water uses: agriculture, tourism, industry and population supply.

Scarcity in deficitary areas had as a first

effect an accused tendency towards over-exploitation of ground water, above its

natural renewal ratio. In the actual

case of ground water, exploitation is at present around 5,500 hm3

per year, that cover 30% of urban and industrial supply and 27% of the

irrigated area. Excessive exploitation of surface water

resources sums up to the impacts produced by ground water overexploitation. This policy brought to the present situation where

Map 5. Density

and distribution of the population.

The effect on the deficit areas.

Table 2. Available

Surface Water Resources in the 13 water regions.

|

Water

Availability (hm3) |

A

1967 |

B 1980 |

C 1990 |

D 1991 |

E 1993 |

F 1998 |

|

Coastal Galicia |

- |

- |

- |

1302 |

1302 |

- |

|

North |

8525 |

7448 |

- |

4967 |

8828 |

- |

|

Duero |

6405 |

9111 |

9465 |

9269 |

7797 |

10229 |

|

Tajo |

4356 |

8343 |

6281 |

6233 |

6233 |

5063 |

|

Guadiana |

2252 |

2462 |

3017 |

2385 |

2963 |

2963 |

|

Guadalquivir |

3564 |

2810 |

4780 |

3255 |

3416 |

3451 |

|

South |

538 |

785 |

533 |

861 |

1109 |

1007 |

|

Segura |

665 |

1317 |

1742 |

700 |

1125 |

1500 |

|

Júcar |

1850 |

3104 |

2003 |

2564 |

3052 |

3437 |

|

Ebro |

8502 |

14133 |

9289 |

9337 |

10727 |

9898 |

|

C.I. Catalonia |

697 |

1656 |

- |

1358 |

1358 |

1587 |

|

|

- |

313 |

- |

312 |

312 |

300 |

|

- |

496 |

- |

496 |

420 |

417 |

a)

Water Resources. II

Social and Economic Development Plan. Presidency of the Government, PG (1967).

b)

National Hydrologic

Planning. Inter-Ministry Commission of Hydrological Planning. MOPU-CIPH (1980).

c)

Hydrologic Plan.

MOPU-DGOH (1990).These data only refer to river basins involving more than one

Autonomous Region.

d)

Water in

e)

PHN Report. MOPT

(1993). It includes over-exploited water tables:

f)

River Basin

Hydrologic Plans (1998).

Table 3. Available

Groundwater Resources in the 13 water regions. Deficits of water

balance.

|

Water

Availability (Hm3) |

Natural reloading

|

Pumping Hm3/year |

% Pumping/Reloading |

% Pumping/total |

Deficit (1) p/r > 1 |

|

Coastal Galicia |

2234 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

North |

8716 |

52 |

- |

- |

- |

|

Duero |

3000 |

371 |

12.4 |

6.7 |

- |

|

Tajo |

2393 |

164 |

6.9 |

3.0 |

- |

|

Guadiana |

750 |

814 |

110 |

14.7 |

240 |

|

Guadalquivir |

2343 |

507 |

21.6 |

9.2 |

10 |

|

South |

680 |

420 |

61.8 |

7.6 |

68 |

|

Segura |

588 |

478 |

81.2 |

8.6 |

215 |

|

Júcar |

2492 |

1425 |

57.2 |

25.8 |

54 |

|

Ebro |

4614 |

198 |

4.3 |

3.6 |

- |

|

C.I. Catalonia |

909 |

424 |

46.6 |

7.7 |

10 |

|

|

508 |

284 |

55.9 |

5.1 |

14 |

|

|

681 |

395 |

58.0 |

7.1 |

32 |

1. Deficit of exploitation units in relation with pumping/reloading >

1

Ratio pumping/reloading Ratio

pumping/total pumping in

Figure 1. Distribution of consumptions

Table 4. Water

consumption in the 13 Water regions.

|

Water Consumtion (hm3) |

Domestic Use |

Industry |

Irrigation |

Refriger. |

Total |

Consumo |

Retorno |

|

Coastal Galicia |

210 |

53 |

532 |

24 |

819 |

479 |

340 |

|

North |

550 |

527 |

532 |

73 |

1692 |

646 |

1046 |

|

Duero |

214 |

10 |

3603 |

33 |

3860 |

2929 |

931 |

|

Tajo |

768 |

25 |

1875 |

1397 |

4065 |

1728 |

2337 |

|

Guadiana |

157 |

84 |

2285 |

5 |

2531 |

2877 |

654 |

|

Guadalquivir |

532 |

88 |

3140 |

0 |

3760 |

2636 |

1124 |

|

South |

248 |

32 |

1070 |

0 |

1350 |

912 |

438 |

|

Segura |

172 |

23 |

1639 |

0 |

1834 |

1350 |

484 |

|

Júcar |

563 |

80 |

2284 |

35 |

2962 |

1958 |

1004 |

|

Ebro |

313 |

415 |

6310 |

3340 |

10378 |

5361 |

5017 |

|

C.I. Catalonia |

682 |

296 |

371 |

8 |

1357 |

493 |

864 |

|

|

95 |

4 |

189 |

0 |

288 |

171 |

117 |

|

|

153 |

10 |

264 |

0 |

427 |

244 |

183 |

Map 6. The Hydrologic basins of

Environment and Protection

Groundwater over-exploitation is among the most relevant environmental

effects of water use in

Risks can be better appreciated in the Eastern Spanish regions, in the

Mediterranean area and the islands (especially the

The situation of subterranean resources has an important repercussion on

surface waters, as it brings to spring , lowering of

basic levels of river flow, reduction of inland wetlands and coast salinisation. The exhaustive exploitation

of surface water resources sums up to the impacts produced by over-exploitation

of ground waters. We have in fact regulation percentages higher than 70

% for the

Spread contamination coming from agriculture, connected to the

increasing use of fertilisers and other chemical like insecticides, is another

worrying danger for

As regards waste water and purification, in spite of the big effort in

infrastructures, it has not been possible to stop degradation of water quality, that affects both human consumption and natural

areas linked to water (wetlands, river borders, etc.). As a reference it is

noteworthy that 60% of water from Spanish rivers is not apt for human

consumption.

To control water quality,

The most affected natural areas, landscapes and ecosystems of interest,

especially those included in the Natura 2000 network,

correspond to:

·

Riverine ecosystems,

especially those located in the Mediterranean areas, which are seriously

threatened.

·

Continental wetlands and lake systems, subjected to

strong impacts caused by water-tables over-exploitation or surface water

depletion.

·

Small wetlands linked to ground water.

·

Lands traditional submitted to irrigation, whose

abandon involves the loss of an important landscape and cultural heritage of

the Mediterranean region, which in several cases also host habitats or species

of regional. national or communitarian importance.

The following table shows the main significant effects linked to water

deficit caused by over-exploitation:

Table 5. Environmental effects

associated with water deficit and water-table overexploitation

|

ECOLOGICAL AND

PUBLIC-USE REPERCUSSIONS |

HYDROLOGICAL EFFECTS

|

|||||

|

Water-table

overexploitation |

Marine Intrusion |

Deterioration of

water quality in water tables |

Reduction of

river contributions |

Deterioration of

surface water quality |

|

|

|

Subsidence

processes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Soil

salinisation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eutrophication of masses of water |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alteration of coastal ecosystems |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Degradation of wetlands (e.g. Daimiel – Doñana) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Degradation of riverine ecosystems |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Loss of biodiversity - water species of animal and plants |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alteration of riparian communities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Degradation of agricultural traditional landscapes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Health-Sanitary risks linked to public river-beds |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Loss of recreational resources linked to water |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Loss of landscapes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Critical effects |

|

|

Serious effects |

|

|

Moderate effects |

|

Water laws and Regulations

With regard to competencies in the field of water, in the Spanish case

we must take into account the complementary, and

sometimes decisive role of the Autonomous regions. Article 149.1.22 of the

Spanish Constitution attributes the State the exclusive competency in the

subject of legislation, planning and concession of resources and water

exploitation when they flow through more than one Autonomous Region. On the

contrary, according with the article 148.1.10, Autonomous Communities can have

competencies on water exploitation projects and construction, and irrigation

channels of interest within their territory. Most Autonomous regions have been

transferred these competencies, which also include subterranean waters.

The Water Law (Ley de Aguas

- 29/1985), is the State’s basic text that regulates

this subject, and only regulates the State’s competencies. Nevertheless, the

exercise of these competencies has to be ruled by the delimitation criterion

used by the Water Law, based on the “river basin” concept, being the

interregional river basins of exclusive competency of the State, with few

exceptions. Law 9/1992, December 23rd, regulates the transfer of

competencies to Autonomous regions. The Water Law disposes that Basin

Administration bodies have to be created for hydrographical basins exceeding

the Autonomous Regions’ territory. These Basin Administration bodies will be

the State’s bodies with competencies on this issue. In

Within this framework, one singularity is the “

The hydrological planning has also the Law rank (Law

10/2001-Hydrological National Plan), and organises a large part of competencies

and functions within the water management scope.

Beside the Water Law, and among a large variety of regulations related

with the use of water, the following ones are worth emphasizing:

·

Water resources for domestic use: Royal Decree

1138/1990: Health-Technical regulation for the supply and quality control of

potable water for public consumption.

·

Regulation of municipal competency with regard to

potable water supply to population, including sewerage (beside the articles of

the Water Law): Basis Laws of the Local Administration.

·

Regulation of the Water Public Domain (R.D. 849/1986, April 11th).

·

Standards to measure the quality of water, including

water contamination by persistent organic pollutants are contained in the Royal

Decree 927/1988.

·

Royal Decree 261/1996, February 16th, on

the protection of water against the contamination produced by effluents from

agricultural sources.

·

Energy aspects related to water are regulated by the

R. D. 2818/1998, about electric power produced by plants powered by renewable

energy sources, waste or cogeneration.

·

Royal Decree (Ley 9/2000) on

Envirronmental Impact Evaluation (including trasvases of but of 100 hm3 /year).

As regards water resource protection, it is integrated by an extensive

legislative repertory referring to the protection of the environment and of

habitats declared protected areas or of community’s interest. The several

national laws (in particular Law 4/1989 about conservation of natural areas and

of wild flora and fauna), are complemented by autonomous regions’ laws, and in

both cases specific regulations on water in protected areas are included.

Special attention is given to forest areas that are providers of water resources,

wetlands (especially SBPZ and RAMSAR sites) and to those sections of rivers

that host a high biodiversity. The Legal

Order attends to and is especially complemented by the Directive 92/43/EEC

regarding conservation of natural habitats and wild flora and fauna, as well as

the Directive 79/409/EEC, relative to wild bird conservation.

Most EC’s directives have been transposed the related legal order, both

with regard to water protection and public health. As an example, there are

more than 20 EC Directives, incorporated to the Spanish legal order regarding

quality requirements of water in function of its use.

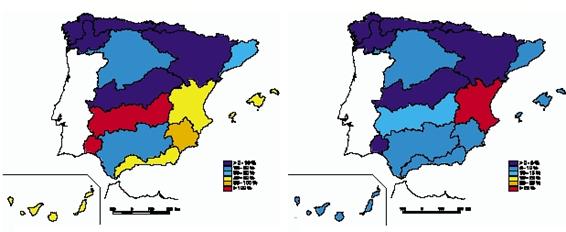

Map 7. Autonomus Regions in

Institutional framework and constraints

The institutional and competency framework of hydrological planning and

water use is structured on the base of the two following instruments:

• The National Hydrological

Plan.

• The Hydrological Plans of

each basin.

The

The National Hydrological Plan, approved by law (Law 10/2001) defines

the competency areas and the water management framework in

The management at the level of each hydrographic

basin is assigned to the already mentioned Basin Administrations, whose

functions are collected within art. 21 of the Law, and are the following:

·

The elaboration of the Basin Hydrological Plan, its

following-up and revision.

·

The administration and control of the public water

domain.

·

The administration and control of the exploitations of

general interest or that affect more than one Autonomous Region.

·

Planning, construction and exploitation of all works

carried out with charge to the own funds of the Administration and those that

have been assigned to them by the State.

·

Those deriving from agreements made with the

Autonomous Regions, Local Administrations and other public or private bodies,

or those signed with privates.

The competency survey closes with the Users' Communities, registered at

the Basin Administration, among which the irrigators' Communities stand out for

their importance. On the other hand, the State Water Society have been created for the

promotion of the hydraulic infrastructures included within the Basin

Hydrological Plans. Their objective is to facilitate the joint intervention of

private and public initiative for the execution and exploitation of the works

carried out in each basin and, in definitive, to optimise the available

economic resources.

One of the characteristics of the institutional conflicts is found in

the disparity of criteria between the Ministry of Agriculture and the Ministry

of the Environment when it is time to elaborate the Basin Plans. An almost

permanent disagreement that rises from the contradiction that who decides water

agricultural uses is not the final responsible for them. A significant example

is given by the clear disconnection between the National Hydrological Plan and

the National Irrigation Plan, presented by the Ministry of Agriculture but not

approved, that plans 250,000 ha of new irrigated lands, while the Basin Hydrological

Plans forecast a total of 1,500,000 ha. On the other hand the viability of new

irrigated lands is not so clear, and it should be questioned to consider them

as the main, or only way of rural development.

Municipalities have competency for potable water supply to the

population and for sewerage. To carry out these services, local bodies can use

the type of management allowed by articles 57, 85 and 87 of the Law of Bases

for the Local Regime. Therefore it can be chosen between a direct management

(by the Local Administration itself, its Autonomous bodies or commercial

societies with exclusive capital), or an indirect management (commercial

societies with majoritarian capital, concessions and

agreements).

It is within Municipal supply that the extreme overlapping and

atomisation of competencies is shown in the clearest and most negative way. The

Administration's uncontrol of the concessionaire

companies' functioning is very high, in a framework where most supply services

with a public management are being transferred to private companies (it does

not exist a national regulation. It is worth reminding that he

process of privatisation is not subjected to any control and in most occasion

it is used to correct deficits, of various origin, of the municipal budgets.

Competency and institutional

overlapping is also shown in cases such as low efficiency of the

purification plants given to municipalities, most of which are unoperational or abandoned after they have been entrusted

to municipalities.

Low bill collecting efficiency sums up to the competency dispersion of

the institutional framework. It is due not only to the same concept of the

economic-financial regime, but also to the low efficiency of the system to

collect exactions (collection is situated around 50% of total billing and in

many cases considerable delays take place). Furthermore, 75% of the water

consumed in

Table 6. Responsible Authorities in

the Water Sector

|

Responsibilities |

Agency/Authority |

|

Planning Regulations |

Ministry of Environment Water National Council

(Consultative) Basin Administrations (Conferederaciones Hidrográficas) Autonomous Regions (A.R.) |

|

Administration and control

of the hydraulic public dominion. |

Basin Administrations

(Confederaciones Hidrográficas) Autonomous Regions (internal

river basins) |

|

Domestic and urban |

Ministry of Environment Ministry of Industry Ministry of Health and Consumption. Basin Administrations Civil Works Administration (A.R) Health Administration (A.R.) Industry Administration (A.R.) Environment Administration (A.R.) Diputaciones Provinciales. Minicipalities as final administration in

charge |

|

Irrigation |

Ministry of Agriculture Ministry of Environment Autonomous Regions Comunidades de

Regantes |

|

Infrastructures |

Ministry of Environment Basin Administrations

(Confederaciones Hidrográficas) State Water Society Autonomous Regions |

|

Purificatin and Re-use |

Ministry of Environment Ministry of Development Ministry of Health and Consumption. Basin Administrations Civil Works Administration (A.R) Health Administration (A.R.) Environment Administration (A.R.) Diputaciones Provinciales. Minicipalities as final administration in

charge |

|

Hydroelectric uses |

Ministry of Environment Ministry of Industry and Energy Basin Administrations Autonomous Regions |

Management, Institutional and policy options

Spanish water policy is found

in the National Hydrological Plan, in the Basin Hydrological Plans and, complemantarily, in the policies and decisions developed at

the level of each Autonomous Region.

The strategic options set forth in the National Hydrological Plan can be

summarised as follows:

Programmed

reduction of demand.

·

Maintenance of present-day water contribution by

inter-basin transfers.

·

Increase in available volumes through a major use of

waste water and modernisation of irrigated lands.

·

Adoption of measures of saving and modernisation of

irrigated lands.

·

Programmed withdrawal, by public initiative, of the

irrigated lands supplied through overexploited water tables which are

unsustainable on the medium-long term.

·

Application of compensatory measures to the affected

collectives.

·

Priority maintenance of water domestic supply.

·

Reduction of losses during water transportation (there

are limit situations that at present are around 50% in large trasvases).

Large-scale

desalination. Covering deficits through large-scale desalination of seawater

complemented by saving and re-use measures:

·

Applications of the measures considered in the

previous option, except the reduction of irrigated lands, incorporating an

additional water contribution from seawater desalination.

·

Maintenance of consumption levels similar to the

present ones, only increased by the new demands of supply.

·

Effective control of the agricultural demand increase

through legal and technical-administrative instruments.

Inter-river basin transfers. Covering deficits

through water transfer from other basins, according with the existing

possibilities, complemented by desalination, saving and re-use measures:

·

Stabilisation of agricultural demand, maintaining

irrigated land area at the same level corresponding to the present-day

situation, through application of legal and technical-administrative

instruments.

·

Adoption of water saving and re-use complementary

measures similar to those contemplated in the previous options.

·

Local seawater desalination for local supply.

·

Inter-basin transfer are

planned following the criterion of minimising both water costs and

environmental effects on the affected river sections and the territories that

host the water-transportation infrastructures.

This last option has generated

the strongest social tensions and environmental contestations between the

different basins. It is worth reminding that the National Hydrological Plan

states in its prologue that “inter-basin transfers should constitute the last

solution".

Beside the multiple

initiatives at the Autonomous regions level, at the State level there is a

group of Programmes and action lines that exemplify the options of future with

regard to water policy and management. We have therefore:

·

The Programme for the improvement and modernisation of

traditionally irrigated lands, whose aim is irrigating water saving,

improvement of water quality, re-use of waste waters and energy saving.

·

As regards sewerage, there is a National Plan of

Sewerage and Waste Water Purification, through which infrastructures for

sewerage and waste water purification are planned, with the aim to achieve by

2005 that urban settlements of more than 2,000 inhabitants will rely on

adequate purification systems. Nevertheless, municipal wastes sum up to 3.500 hm3/year approximately, of which more than 700

are directed to the sea. In these moment re-use of

waste water is close to 100-150 hm3/year, and constitute one of the most

delicate points to resolve as regards sustainable management of water resources,

due to the high degree of competency disorder.

Furthermore a number of

awareness promotion campaigns on sustainable use of water have been carried

out, although their repercussion at a national level is of little significance.

On this line it is necessary to include the impact of the new municipal,

large-reaching initiatives such as the implementation of local Agendas 21, that

include programmed

improvements regarding water sustainable use and water quality.

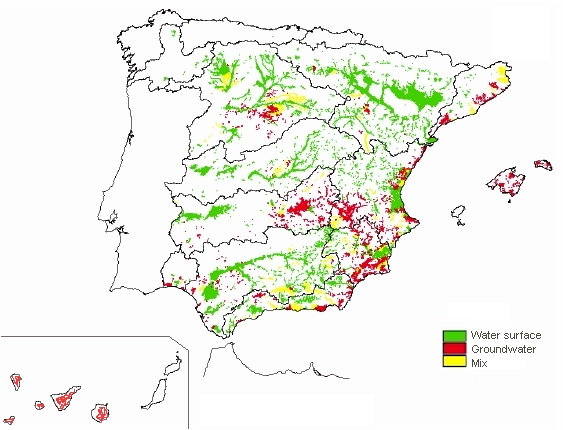

Map 8. Distribution

of the irrigated land. Water source.

Map 9. Distribution

of the water deficit (all concepts).

Table 7. Constraints facing the water

sector

|

Category |

Constraints |

|

Natural |

Unequal water spatial

distribution. Uneven precipitation

distribution, spatially and temporally. Dependence on transboundary waters. High sensitivity and risk of

loss of the aquatic ecosystems. Frequent droughts. |

|

Human |

Tendency - distribution of

population towards deficit areas. Tourist influx is uneven in

space and time. Excessive water consumption

for irrigation. Demand peaks in the dry

season. Groundwater and surface

water is contaminated by pollutants. Spread contamination coming

from agriculture. Overexploitation of

underground aquifers. Irrigation of unsuitable or nonprofitable cultures. Lack of environmental

awareness. |

|

Technical |

Technological incapacity of

the local authorities and particularly maintenance of water infrastructure. Old distribution networks

with high losses (average 50 years) Complexity of transvases. Lack of proper irrigation

techniques that would save water. Low efficiency of the

purification systems. Little technological diversification. Illegal connections to the

networks. Absence of control (60% of

water not entered). Use of conventional energy

sources for the massive desalination. Lack of information on new

technologies for water saving and management |

|

Financial |

Water pricing is politically

influenced and not based on water cost, leading to inadequate finances for the

funding of further infrastructure. Inadequate prices for final

uses in sectors like the tourism and the new cultures - competition with

other traditional sectors. Deficient allocation of

funds to the remote regions. Serious difficulties for the

application and collection of the “spill canon”. Noninclusion of environmental

externalities. Destiny of the financial

collection for aims different from the water. |

|

Administrative and Institutional |

Overlapping and atomisation

of competencies (e.g. urban supply). Lack of coordination among

responsible authorities. Lack of participation of key

water actors in the Basin Administrations. Undefinition of the roll of

the Users Communities. Lack of convergence of the sectorial

policies. Absence of homogenous criteria in the privatization

processes. Lack of citizen

participation. |

Table

8. Water

Resources Planning Matrix

Activity

|

Municipal Authority/ Water

Utility |

Autonomous Regions |

River basin authorities |

Users Communitiess |

Ministry of Environment |

Ministry of Agriculture |

Ministry of Industry |

Surface

water

Use Storage Recharge Diversion Quality monitoring Assessment |

X X X |

X X X X X X |

X X X X X X |

X X |

X X X X X |

X X X |

X X X X |

Ground

water

Use Storage Recharge Quality monitoring Assessment Well/drill permits |

X X X |

X X X X X X |

X X X X X |

X X |

X X X X X |

X X X |

X |

Irrigation

network

Rehabilitation Modernization |

|

X X |

X X |

X X |

X X |

X X |

|

Reuse

Drainage water Wastewater |

X |

X |

X X |

|

X X |

X |

|

Desalination

|

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

Introduction

of technology |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

|

Efficient water utilization Domestic Industrial Irrigation |

X |

X X X |

X |

X |

X X X |

X |

X |

Legislation

Regulation and codes Standards |

X |

X X |

|

|

X X |

X X |

X X |

Policy setting

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Water

allocation |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

Project

financing |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Project

design |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

Project

Implementation |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

Operation

and maintenance |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

Pricing

|

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

|

Enforcement

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Water

Data records |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

Selection of

Representative Regions

Among the areas and regions affected by water resource deficiency, which

fall within the arid and semiarid areas scope, two spaces have been selected,

in view of their representative social, environmental and economic features.

Map 10. Selected

regions.

1.

The

Map 11.

2.

Doñana, region and connected hydrographic

basins. The wide region of Doñana and its

surroundings represents at present an authentic paradigm as regards water resource

management, planning and assignment. It hosts the most important wetland of

Europe, the Doñana National Park (Ramsar and World Heritage site), but at the same time its

surroundings host a population of more than 100,000 inhabitants, whose activities

(fundamentally recently introduced agriculture) progressively clashes with the

requirements needed to maintain the seasonal water levels for the wetland

conservation. The programme Doñana 2005 and

the Sustainable Development Plans of the Doñana

surroundings try to face the dilemma between conservation and development in a

framework of water scarcity and progressive alteration of water tables in an

area where quality of water, both for human consumption and for the

conservation of basic ecosystems, is a serious problem.

Figure 2. Orthophoto of the Doñana region.

Due to their geographic localisation, close to the Tropic of Cancer, the

In spite of that, the Canaries are poor in freshwater resources. The

extent of their own freshwater resources, 177 m3 per inhabitant per

year, place them in the last place within the Spain classification by

hydrographical river basins, and this number is very far from the national

average of 1,389 m3/pers./year. With a population near to 1.5 million

inhabitants, the islands host every year more than 10 million tourists whose

average daily water consumption is of 350 l/pers./day

(Insular Hydrologic Plans). This increasingly pronounced difference between

resource availability and consumption is one of the present-day most relevant

characteristics of the archipelago. Rainfall in the Canary archipelago is very

scarce (an average of 310 l/m2/year) and irregular, both in time and

space.

Topographic difficulties and permeability of the existing geologic

materials lead to the exploitation of only a minimum share of the surface water

resources. It is explanatory enough that the volume of water retained by the

some 100 dams built to this end (41 hm³/year), only

reaches the 33% of their total capacity.

A relevant feature of subterranean water management is the fact that

they are private property, a singularity in

Another important feature that affects especially the Eastern islands is

the progressive dependence from desalinated water, which is greatly increasing

every year. An extreme case is the

Agricultural consumption is a priority on islands like

One of the most distinctive features of water consumption for

agriculture refers to the generalised presence of intensive crops characterised

by a high demand. Banana plantations –representative crop and main consumer of

water in the Canary archipelago-, is characterised by water demands around

11,350 and 14,850 m3/Ha/year. These crops receive subventions in the

framework of the European Agricultural and are important producers of

landscapes that have progressively have reached a crisis point, similarly to

other productions, because of conflicts with tourist and urban demand and the

as a consequent rise in water price, since the private character o the canary

water market.

The unforeseeable population growth of the last years causes strong

uncertainty as regards water resource planning. In only five years the foreign

population growth doubled the natural growth rate. A similar tendency is

detected in the tourist sector, where the tourist lodging capacity has

practically doubled itself in the period 1998-2001.

As regards sewerage, we also find important deficits, especially among

the dense scattered settlements of the islands, which directly influence

subterranean waters due to contamination of water tables. Only the two main

islands rely on acceptable grids although they also have significant

deficiencies in specific settlements. The remaining ones have serious

deficiencies regarding sewers or pour too large quantities of surface or

subterranean wastewater.

With regard to water purification, serious competency conflicts have

also been detected in tuning and maintenance of the purification systems that

at present have a very low operational rate (close to 30%). Scattered

purification systems are a distinctive feature of the Canary situation. Price

policy of purified water, public owned, is also characterised by its

variability and inconsistence. In

Water quality for urban supply followed a descending curve in the last

years. Following-up carried out by the different hydrological plans detects

negative effects in the quality of subterranean waters, to which those derived

from hydrogeologic situations that present specific

water tables characterised by a high fluor content

have to be added.

Public management, especially the local one, faces serious difficulties

for a sufficient and efficient implementation. Difficulties have to do with,

from one side, budget origin and destination, without forgetting financial

collection; from another side with the politic price of cost transfer to users,

the progressive rise in price of the higher number of services required, and

lastly with the population to serve, characterised by a very high growth rate

or by depopulation. All this has an influence on scale economies or

diseconomies.

The studies: SPA-15, Canarias Agua 2000, Mac 21, advances of several Insular Hydrological

Plans ,

Within this context, the strategy of the Canary Islands Hydrological

Plan is founded on the following principles:

·

To promote a sustainable use of water resources on the

basis of a medium-large term planning.

·

To protect water ecosystems as an essential principle

for a sustainable development.

·

To guarantee a qualitatively and quantitatively

appropriate water supply to achieve a sustainable development.

·

To achieve the economic efficiency of water offer and

use compatibly with social and environmental dimensions.

·

Congruence between economic and environmental criteria

and the design of an integrated management system, with a prudent use of

regulatory and market processes.

·

To advance in setting up innovatory and realistic

policies on endowment and prices.

To these criteria some considerations of the Infrastructure Director

Plan within the section regarding water resources:

·

To improve knowledge about natural resources, setting

up an automatic control network within the whole region that allows the

following-up of comparable data and the establishment of a sound basis to

achieve and maintain a sustainable use of the public water domain.

·

To protect quality and guarantee renovation of the

different sources of production.

·

To optimise the implementation of systems for

non-conventional resource production.

·

To intervene in sewerage and supply infrastructures.

Figure 3 .

Evolution of water demand (perspective – year 2000)

Source:

Figure 4 .

Evolution of water production (year 2000 perspective)

Sïurce:

Table

9.WATER BALANCE

|

Concept/Island |

FUERTEVEN (1) |

LA GOMERA |

GRAN CANARIA |

EL HIERRO |

LANZAROTE |

LA PALMA |

|

|||||||

|

Hm3 |

% |

Hm3 |

% |

Hm3 |

% |

Hm3 |

% |

Hm3 |

% |

Hm3 |

% |

Hm3 |

% |

|

|

Precipitation |

16 |

100 |

140 |

100 |

466 |

100 |

95,3 |

100 |

127 |

100 |

518 |

100 |

865 |

100 |

|

Evapotranspiration |

s.d. |

- |

69 |

49,3 |

304 |

65 |

69 |

72,4 |

122,2 |

96 |

238 |

46 |

606 |

70 |

|

Surface water |

4 |

25 |

11 |

7,8 |

75 |

16 |

0,3 |

0,3 |

1,3 |

1 |

15 |

3 |

20 |

2 |

|

Infiltration |

12 |

75 |

60 |

42,9 |

87 |

19 |

26 |

27,3 |

3,3 |

3 |

265 |

51 |

239 |

28 |

|

Sources: Advance of island

hydrological plans. 1. s.d.- without data

available |

||||||||||||||

Table 10. WATER

BALANCE

|

|

FUERTEVENT. |

LA GOMERA |

GRAN CANARIA |

EL HIERRO |

LANZAROTE |

LA PALMA |

TENERIFE |

|||||||

|

PRODUCTION |

Hm3 |

% |

Hm3 |

% |

Hm3 |

% |

Hm3 |

% |

Hm3 |

% |

Hm3 |

% |

Hm3 |

% |

|

Surface water Small dams |

2,6 |

21,3 |

3,4 |

24,3 |

11 |

8,5 |

- |

- |

0,07 |

0,7 |

5 |

7 |

1 |

0,5 |

|

Groundwater |

5,3 |

43,5 |

10,6 |

75,7 |

98 |

75,4 |

1,45 |

100 |

0,2 |

2,3 |

68 |

93 |

211 |

99,5 |

|

Desalination |

4,3 |

35,2 |

0 |

- |

21 |

16,1 |

- |

- |

9,6 |

97 |

0 |

- |

0 |

- |

|

Re-use |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

s.d. |

- |

0 |

- |

s.d. |

- |

|

TOTAL |

12,2 |

100 |

14 |

100 |

130 |

100 |

1,4 |

100 |

9,9 |

100 |

73 |

100 |

212 |

100 |

|

Sources: PPHH of La

Palma, La Gomera y El Hierro. Hydrological Plans of Tenerife and Lanzarote;” Las Aguas del 2000” - y PIO Fuerteventura. s.d.- without data

available |

||||||||||||||

Table 11. WATER CONSUMPTION BY CATEGORY

|

|

FUERTEVENT.

|

LA GOMERA |

GRAN CANARIA

|

EL HIERRO |

LANZAROTE |

LA PALMA |

||||||||

CONSUMPTION

|

Hm3 |

% |

Hm3 |

% |

Hm3 |

% |

Hm3 |

% |

Hm3 |

% |

Hm3 |

% |

Hm3 |

% |

|

Irrigation

- Agriculture |

8,4 |

61,8 |

6,1 |

43,3 |

75 |

58 |

1,2 |

85,7 |

0,3 |

6 |

58 |

79,5 |

109,2 |

52,7 |

|

Domestic

and Services |

2,7 |

19,8 |

6 |

42,6 |

38 |

29 |

0,2 |

14,3 |

2,4 |

52 |

6 |

8,2 |

62,7 |

30,2 |

|

Tourism |

2,5 |

18,4 |

- |

- |

15 |

11 |

- |

- |

1,4 |

31 |

- |

- |

14,1 |

6,8 |

|

Industrial |

- |

- |

2 |

14,1 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

- |

0,5 |

11 |

2 |

2,8 |

5,3 |

2,6 |

|

Resources

nonused |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

6,9 |

9,5 |

4,5 |

2,2 |

|

Losses

in trasvase |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

11,5 |

5,5 |

|

TOTAL |

13,6 |

100 |

14,1 |

100 |

130 |

100 |

1,4 |

100 |

4,6 |

100 |

72,9 |

100 |

207,3 |

100 |

|

Sources: PHH La Palma, La Gomera, El Hierr, Tenerifeandy Lanzarote; “Las Aguas del 2000”. |

||||||||||||||

Figure 5 . Percentage water

consumption of the tourist sector on each island

Source:

Figure 6 . Tourism water

supply and desalination

Source:

Figure 7 . Evolution of water

production and population demand (perspective). Gran Canaria Case.

Source:

Table 12: Growth

in tourist accommodation. 1986-1996.

|

Year |

Tourists |

Rooms |

|

1986 |

4,169,050 |

201,493 |

|

1987 |

5,068,242 |

251,067 |

|

1988 |

5,416,652 |

308,177 |

|

1989 |

5,352,205 |

343,559 |

|

1990 |

5,459,473 |

364,269 |

|

1991 |

6,136,990 |

375,995 |

|

1992 |

6,327,112 |

337,482 |

|

1993 |

7,551,065 |

337,975 |

|

1994 |

9,256,817 |

330,614 |

|

1995 |

9,693,086 |

324,124 |

|

1996 |

9,804,540 |

328,254 |

Source: White Paper

on

Table 13.

|

Natural conditions and infrastructure |

Regional Context

|

Climate

Type |

Oceanic Type: Mediterranean Template |

|

Aridity

Index |

0.2 < AI < 0.6 coastal and oriental islands |

||

|

Permanent

Population |

1781366 (+331000 Tourist/average) |

||

Water availability

|

Total

Water Resources /Availability (hm3) Groundwater Surface water |

702 78 |

|

Water quality

|

Quality

of surface water |

Good |

|

|

Quality

of groundwater |

Average |

||

|

Quality

of coastal water |

Poor |

||

Water Supply

|

Percentage

of supply coming from: -

Groundwater -

Surface water -

Desalination |

87% 5% 8% |

|

|

Network

coverage: - Domestic - Irrigation - Sewerage |

60% 85% 60% |

||

|

Economic and Social System |

Water use

|

Water

consumption by category: -

Agriculture -

Domestic and services -

Tourism (only accommodation) -

Industrial -

Non-used resources -

Losses (internal network) |

58% 27% 7% 3% 2.5% 2.5% |

|

Resources

to population index |

438 |

||

Water demand

|

Water

Demand trends |

Variable - Increasing |

|

|

Consumption

index |

53% |

||

|

Exploitation

index |

58% |

||

Pricing system

|

Average household budget for

domestic water

(pa) |

356 € (Average price 1,55 m3) |

|

|

Average household budget for

agricultural water |

Variable |

||

|

Average

household income |

16800 € |

||

|

Cost

recovery |

Average |

||

|

Price

elasticity |

Average |

||

|

Social capacity building |

Public

participation in decisions |

Poor |

|

|

Public education on water

conservation issues |

Poor |

||

|

Decision Making Process |

Water Resources Management |

Water

ownership -

Groundwater -

Surface water |

Mostly private Public and private |

|

Decision making level

(municipal, regional, national) regarding: -

Water supply for each sector -

Water resources allocation for each sector |

Regional - Local Regional - |

||

Water Policy

|

Local

economy basis |

Tourism |

|

|

Development

priorities |

Tourism |

4.

Doñana and its surroundings

constitute a natural space featuring the widest variety of pressures regarding

the use and assignment of water resources. As a territory in which the most

important European wetlands coexist, the

Doñana could be considered to be an

excellent laboratory for studying the management of water resources, a place

where all the preservation and development strategies applied during the last

decades share the difficulties of managing water resources.

Regarding the policies of preservation and management of water

resources, the plans have entirely focused on the

Around this sanctuary of the European biodiversity is the Natural Park

of Doñana and its Surroundings, located in the

municipalities of Almonte, Hinojos,

Lucena del Puerto, Moguer

and Palos de la Frontera (province of Huelva), Sanlúcar de Barrameda (province of Cádiz),

Puebla del Río, Aznalcázar, Villafranco

del Guadalquivir and Villamanrique

de la Condesa (province of Seville). This extended

list is representative to the administrative and territorial complexity of the

area.

The territory occupied by Doñana’s

basins, which also includes the National and

The agricultural development in the area arrives at a later stage due to

its hard conditions: the XIX century witnessed a series of failed efforts

oriented to drying the salt marsh. By the end of the 1920’s, the area devotes

itself to massive rice crops, which nowadays occupy over 35,000 ha, thus

becoming a factor of pressure for the National Park.

After this episode, in the 1970’s, the FAO generates a report that

results in the creation of a Plan for Agricultural Development in Almonte-Marismas (decree 1194/71), driven by a

development-oriented mentality that resolves to declare it an Area of National

Interest. This is the consolidation of 45,960 ha of crops; 30,000 of which

correspond to irrigated land. This strategy is based on recognising the

existence of an important water table in the area. Nowadays, the useful surface

for irrigation sums up to approximately 14,000 ha.

Regarding the agricultural exploitation, we must highlight de importance

of the strawberry trees, which occupy some 2500 ha, and constitutes a very

concentrated source of employment. The exploitation of groundwater does not

directly affect the water supply of the National Park, although it does affect

the quality of underground waters, which sometimes feature nitrate

concentrations of more than 50 mg/l.

The tourist activity, mainly concentrated on the area of Malascañas, located at the border of the National

Park, is also a factor of pressure for water resources, especially during times

of drought. Matalascañas offers a tourism

capacity of 63,233 people, with a high level of concentration during the high

season.

All these episodes resulted in an alteration of the water regimes, followed

by a serious overexploitation of groundwater and manipulation of superficial

water systems, which have seriously endangered the preservation of the

This has lead to a progressive recognition of the fact that the

preservation of the National Park is not only an obligation brought about by

the need to preserve this important natural sanctuary, but also of the fact

that Doñana is a patrimonial value which

cannot be dissociated from the future economy of the area. This concern has

resulted in the implementation of several strategies oriented to the

sustainable management of water resources. In this sense, we must highlight the

International Experts Commission’s Report about the Development of Strategies

for the Sustainable Development of Doñana in

1992. This report has inspired many of the principles for the alternative

management of water resources during the last years.

But in 1998, Doñana faces one of its worst moments due to the

breaking of a pyrite pond belonging to a mining exploitation,

that caused the flooding of more than 2600 ha with high metal content muds. Although the muds did not

reach the park itself, this accident caused red alert within all

administrations and the whole society. After an impressive deployment of technical

and human resources, the muds could be removed

avoiding an ecological catastrophe with unforeseeable consequences.

What at the beginning appeared

to be one more regrettable accident due to lack of planning and foresight in

natural areas management turned to be the start of one of the most important

wetland regeneration initiatives ever carried out in the whole planet. In reply

to this situation, the big water regeneration programme named “Doñana 2005” was started, supported by the Spanish

Ministry of Environment, whose immediate environmental actions were funded with

some 140 million €. It is a project whose objectives are a lot more ambitious

than providing the mere solution of the problems caused by the accident. It is

also complemented by another important action called “the Green corridor of Doñana”, supported by the “Junta de Andalucía” that will be carried out within the

buffer zone.

Hydrological

characteristics

The area is divided into two

domains:

a)

The salt marsh. Is a very plain area that combines

periods of flood and drought. Its main sources of

water are the rivers and tributaries and, in a smaller proportion, some few

emergencies of underground water running through pipes.

b)

The rest of the territory is basically made up of

sand. This is the area where water precipitations overload the water table

(called water table 27). It holds most of the water demanding activities.

On the overall system, the

role and the alteration of underground waters is one of the fundamental

problems for the management of this resource in the area. As in many other groundwater, overload is one the factors where estimations

are more subject to error. The figures range from 50 to over 200 mm/year.

The challenges

The conflict between

preservation and a balanced leverage of water resources in Doñana

materializes with the solving and recognition of the following aspects:

a)

The overexploitation of groundwater is seriously

affecting natural areas of vital importance. The effects of overexploiting the

underground waters in the ecosystems seem to be put off with the years.

Nowadays, a great portion of the water table under the salt marsh has fallen

from a 1-meter level over the ground to a 2-meter fall under its own level.

b)

Overexploitation is starting to allow the entrance of

the salty waters contained in the sediments of the salt marsh, with a

considerable impact on the quality of waters.

c)

The massive usage of fertilizers in the main

agricultural activities has a devastating effect on the quality of the waters.

d)

The organic contribution due to domestic tributaries

also adds to the problem, since the network of cleansing stations is still to

be completed.

e)

The agricultural and industrial residues, especially

the vegetable waters derived from olive manipulation, results in scattered

episodes of contamination in large brooks.

f)

The original water

system of the salt marsh is deeply altered. For many years, a series of

corrective actions have tried to balance the complex system of the salt marsh.

A considerable part of the Doñana Programme

2005 is oriented to regenerating the hydrological systems for the basic

functions of the salt marsh and its compatibilization

with human needs.

Table 14. Doñana Matrix

|

Natural conditions and infrastructure |

Regional Context

|

Climate

Type |

|

|

Aridity

Index |

0,4<AI<0.65 |

||

|

Permanent

Population |

180000 (+75000 Tourist

seasonal/average) |

||

Water availability

|

Total

Water Resources /Availability (hm3) -

Groundwater - Surface water |

Min: 155 hm3/year Max: 425 hm3/year Min: 32 hm3/year Max: 78 hm3/year |

|

Water quality

|

Quality

of surface water |

Average |

|

|

Quality

of groundwater |

Average |

||

|

Quality

of coastal water |

Average |

||

Water Supply

|

Percentage

of supply coming from: -

Groundwater -

Surface water -

Desalination |

97% 3% 0% |

|

|

Network

coverage: -

Domestic -

Irrigation -

Sewerage |

95% 95% 60% |

||

|

Economic and Social System |

Water use

|

Water

consumption by category: -

Agriculture -

Domestic and services -

Tourism (only accommodation) -

Industrial -

Non-used resources -

Losses (internal network) |

84% 4% 8% 1% 3% 30% |

|

Resources

to population index |

|

||

Water demand

|

Water

Demand trends |

Variable - Increasing |

|

|

Consumption

index |

53% |

||

|

Exploitation

index |

Max: 49% |

||

Pricing system

|

Average household budget for

domestic water

(pa) |

50 € |

|

|

Average household budget for

agricultural water |

8114 € Consumption 7000m3/ha size property average = 10

ha |

||

|

Average

household income |

7.535 € |

||

|

Cost

recovery |

Average |

||

|

Price

elasticity |

Fix |

||

|

Social capacity building |

Public

participation in decisions |

Higth |

|

|

Public education on water

conservation issues |

Average |

||

|

Decision Making Process |

Water Resources Management |

Water

ownership -

Groundwater -

Surface water |

Public and private Public |

|

Decision making level

(municipal, regional, national) regarding: -

Water supply for each sector -

Water resources allocation for each sector |

Regional - Local Basin |

||

Water Policy

|

Local

economy basis |

Agriculture Tourism |

|

|

Development

priorities |

Intensive Agriculture Tourism |