Report on the Israeli Water Economy: General Description and Data

Introduction and General Background

Existing Conditions of

The Israeli water economy is in the midst of a severe

crisis whose main features are:

1. Freshwater[1] deficit:

Emanating from a decline in sources (

2. Deterioration of water quality: Continual salination of the coastal aquifer due

to seawater intrusion caused by over-pumping. The over pumping caused a severe

decline in the water levels. This is particularly prominent in the

3. Environmental crisis: The rivers and the

·

Over-pumping of the aquifers, resulting in water level

decline and salinity.

·

Some

decline in the natural renewal of the aquifers due to climatic changes in the

eastern Mediterranean region. The observed phenomena include:

1. Increase in extremes and differences: More drought years,

more very rainy years, and fewer years with average precipitation.

2. Reduction in precipitation in northern

4. "Hydropolitics” – The Israel water

system is very vulnerable to public-political pressure, with the agricultural

lobby in the forefront.

5. Population growth and economic development, resulting in

increased domestic and industrial consumption. These demands are rigid and have

not been accompanied by an increase of sources and/or a reduction of the more

flexible needs of the agricultural sector.

6. Increase in the demands of neighboring entities following

political agreements (Jordan and the Palestinian Authority (PA)).

7. Public-political-economic debate regarding water allocation

and pricing: Essentially, the debate is divided between the economic approach

(Ministry of Finance) that calls for allocation based on a price system that

includes the shadow price of water on the one hand, and the agricultural sector

that requests quota-based allocations and water price adjustments based on

ability to pay, i.e., subsidy, on the other hand. In practice, a combined and

non-uniform allocation system developed, based on tiered prices and quotas.

8. Continuing impotence of the regulator – the Water

Commission (linked to hydropolitics). In 1996 the Water Commission was

transferred from the Ministry of Agriculture to the Ministry of Infrastructure.

The purpose of this transfer, inter alia, was to reduce sectoral considerations on the water economy. The

move had limited effect and did not prevent the crisis.

9. Noncompetitive structure of the system for allocating water

to consumers – the strong centralized system of the government company, Mekorot, and its powerful workers’

committee. Mekorot supplies more

than half the water in

10.

Divergence among the government and the public authorities

that control the water economy (with obvious conflict of interests arising among

them).

11.

Lack of

synchronization of the different needs that the water economy has to

fulfill.

12.

Neglect, apathy, lack of awareness and minimal enforcement

regarding environmental-ecological concerns.

An analysis of the processes that characterize

·

The main quantitative expression of the crisis is the

severe reduction in the ability to produce freshwater from the aquifers (approx.

500MCM) without operating additional wastewater reclamation systems and

desalination plants.

·

The agricultural sector bears the brunt of the cuts (since

the demand of the other sectors is rigid). Its allocation was recently reduced

by about 40%.

·

The strategy for stabilizing the water economy is based on

intensifying desalination of seawater and reclaiming wastewater for agricultural

purposes. At the same time, hydrological rehabilitation of the natural aquifers

(reduction of the hydrological deficits) will not allow increased pumping as was

customary prior to the crisis, and apparently one of its causes.

·

These processes have implementation limitations.

Consequently, in the medium term the water mix at the disposal of the

agricultural sector will be altered (which will influence its geographical

distribution) and its overall consumption will not increase.

·

In the long term, assuming that reasonable quantities will

be desalinated, the agricultural sector will only revert to its pre-crisis

size.

·

The significance for the agricultural sector is a sharp

drop in fresh water allocated for export crops, particularly:

|

Citrus |

120 MCM |

|

Cotton |

70 MCM |

|

Avocado and others |

10 MCM |

|

Total reduction |

200 MCM |

These crops use mainly recycled wastewater. The water made

available by reducing these crops can be redirected for growing vegetables for

the local market and feed for dairy farming.

As a result of the population growth and the stagnation of

crop yields (in comparison to the pre-crisis years), fresh vegetable food

imports will probably increase.

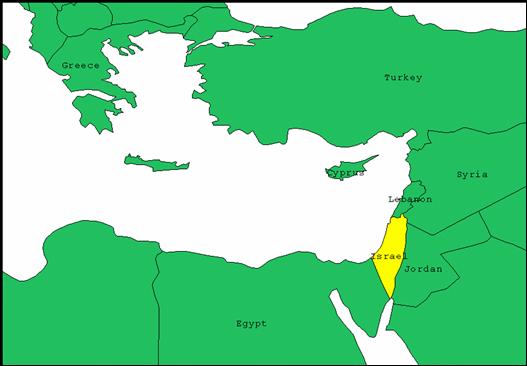

A brief description of Israel

Map No. 1. Geographic

location of Israel

The hills of

Extending about 195 km along the Mediterranean, the coastal

plains range from a width of less than 1 km to a maximum of about 32-km. They

consist of the Plain of Zevulun,

extending about 16 km north of Haifa along the Bay of Haifa; the Plain of

Sharon, extending south from the vicinity of Haifa to Tel Aviv; and the Plain of Judea,

from Tel Aviv to the city of Gaza. The coastal plains contain most of

The

The chief

The coastline of

The climate of

Climatic Indicators

|

Region |

Average temperature (°C) |

Precipitation (mm rain) | |

|

|

Winter |

Summer |

1998-1999 |

|

Coastal: 1. North 2. Center 3. South |

13° 14° 15° |

27° 27° 27° |

534 284 157 |

|

Mountain: 4. 5. |

9° 9° |

25° 26° |

453 264 |

|

Valleys: 6. Jezreel 7 Hula 8. Beit Shean |

15° 15° 17° |

28° 28° 30° |

345 261 106 |

|

Southern: 9. Beer-Sheva 10. Eilat |

17° 22° |

28° 32° |

64 25 |

Population

Population data

(Source: New Master Plan for the Water Economy of Israel,

January 2002, hereinafter: (1) )

|

Year |

Population (millions) |

Annual Rate of Increase |

|

1998 |

6.041 |

|

|

2000 |

6.200 |

1.3% |

|

2010 Projected |

7.295 |

1.6% |

|

2020 Projected |

8.600 |

1.6% |

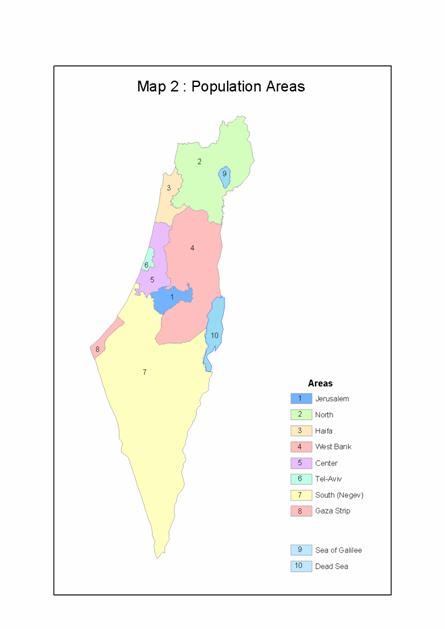

Geographic distribution of

population

Source: Statistical Abstract of

|

District |

Population |

Area of District | ||

|

|

(Thousands) |

% |

Sq. kilometers |

% |

|

1. |

711 |

11 |

652 |

3 |

|

2. North |

1042 |

16 |

4478 |

21 |

|

3. |

840 |

13 |

863 |

4 |

|

4.Center |

1530 |

24 |

1276 |

6 |

|

5. Tel Aviv |

1301 |

20 |

171 |

1 |

|

6. South |

841 |

13 |

14231 |

65 |

|

7. |

172 |

3 |

|

|

|

TOTAL |

6437 |

100% |

21671 |

100% |

* Jewish population only

Distribution of population by type

of settlement

|

Type of Settlement |

Population (in millions) | |

|

|

Millions |

% |

|

3 metropolitan areas (Pop. exceeding 200,000) |

1.5 |

23 |

|

9 big cities (Pop. 100,000-200,000) |

1.4 |

21 |

|

Mid-sized cities (Pop. 20,000-100,000) |

1.7 |

26 |

|

Small towns and cities (Pop. 2,000-20,000) |

1.2 |

19 |

|

Villages and communities |

0.7 |

11 |

|

TOTAL |

6.4 |

100% |

Economic Indicators

General

characteristics

The Israeli Economy – Facts and

Figures*, 1986 to 2001

(Source: Bank of

|

|

1986-1989 |

1990-1992 |

1993-1996 |

1997-1999 |

1999 |

2000 |

2001 |

|

Average population (thousands) |

4407 |

4911 |

5473 |

5974 |

6121 |

6283 |

6437 |

|

Population growth rate (%) |

1.6 |

4.3 |

2.6 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

2.6 |

2.4 |

|

Employed Israelis (thousands) |

1420 |

1573 |

1900 |

2083 |

2137 |

2221 |

2270 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

GDP (in billions of |

260 |

307 |

373 |

429 |

429 |

468 |

465 |

|

GDP growth rate (%) |

3.6 |

6.4 |

5.5 |

2.9 |

2.6 |

6.4 |

-0.6 |

|

GDP/capita (in thousands of US$, current prices) |

8.7 |

12.1 |

15.1 |

17.1 |

16.7 |

17.9 |

17.2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Unemployment rate (%) |

7.1 |

10.5 |

7.8 |

8.3 |

8.9 |

8.8 |

9.3 |

|

Inflation rate (over the year, %) |

18.2 |

15.0 |

11.1 |

5.6 |

1.3 |

0.0 |

1.4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Current account deficit (% of GDP) |

0.2 |

1.1 |

4.8 |

2.7 |

2.9 |

1.2 |

1.5 |

|

Foreign currency balances (in billions of $) |

5.2 |

6.2 |

8.6 |

22.3 |

23.2 |

23.8 |

24.1 |

|

Net foreign debt (% of GDP) |

47.0 |

28.5 |

24.2 |

12.2 |

9.9 |

6.4 |

3.9 |

* Annual averages

The business sector in

Source: Bank of

|

Sector |

Percentage of GDP |

|

Industry |

23.9% |

|

Agriculture and gardening |

3.3% |

|

Transportation and communications |

12.2%* |

|

Construction |

6.6% |

|

Commerce and services |

51.2% |

|

Electricity and water |

2.8%* |

|

TOTAL |

100.0% |

* Infrastructure sectors

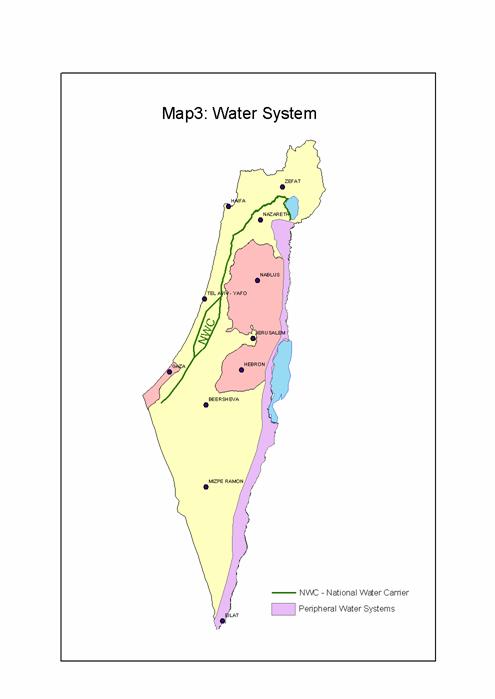

Division into Water Regions

In principle,

Freshwater

The National Water Carrier (NWC) connects all major sources of freshwater into a

single network (see Map 3). Water can be transferred from one region to another,

so that water from one aquifer may be used in a different geographical region.

In addition to the NWC which

transfers water from the

·

Connection of the coastal aquifer (in the west) to the

·

Connection of the NWC to the Northern Coastal Plain and

·

Connection of the

Recycled water

The Shafdan,

a plant for the treatment of urban and industrial effluent of the greater Tel

Aviv metropolitan area (which includes more than 30% of the country’s

population), is responsible for transferring recycled water to the southern

region (Western and

Two large additional networks convey recycled effluent from

the

Pricing policy

Water prices by quality and sector (agricultural,

industrial, urban) are more or less uniform throughout the country.

However, for the sake of convenience only two sub-regions,

Tel-Aviv and the Arava, were

selected for the current study. Detailed description of these regions is

presented in section G below.

Water institutions

According to the Water Law of 1959, all water in

Some 65% of the water in

A small number of regions are not linked to any of the

aforesaid water systems. They are mainly in the east, and include the

Water Demand and Supply

Water Demand

Domestic Demand for Water (MCM/year) (1)

|

Year |

m3 / capita |

National System Demand |

Peripheral System Demand |

Total Demand |

|

1998 |

115 |

669 |

25 |

694 |

|

2000 |

110 |

659 |

25 |

684 |

|

2002 Estimate |

108 |

655 |

25 |

680 |

|

2010 Projected |

120 |

844 |

31 |

875 |

|

2020 Projected |

130 |

1080 |

40 |

1120 |

Industrial Demand for Water (MCM/year)(1)

|

Year |

Freshwater |

Saline Water |

Recycled Water |

Total | ||

|

|

National System Demand |

Peripheral System Demand |

Total Demand |

|

|

|

|

1998 |

91 |

2 |

93 |

36 |

0.2 |

129 |

|

2000 |

93 |

2 |

95 |

37 |

0.2 |

132 |

|

2002 Estimate |

92 |

2 |

94 |

37 |

0.4 |

131 |

|

2010 Projected |

107 |

3 |

110 |

44 |

13.0 |

167 |

|

2020 Projected |

126 |

4 |

130 |

51 |

16.0 |

197 |

Agricultural Consumption

Background

a. The agricultural sector bears the brunt of the drastic cuts

in water supply mandated by the water crisis and the decline in freshwater

supply from 1998 to 2002. (1998 represents an average year, and data for 2002

reflect the situation after several drought years.)

b. The government has decided to allocate 1150 MCM/year to the agricultural sector,

composed of 530 MCM/year

freshwater and the rest, recycled and saline water.

c. It is estimated that the aquifer deficit and Mekorot’s ability to develop new water

(desalination and recycling) will enable achieving the aforesaid goal only in

2010.

d. Future agricultural demand will probably be strongly

affected by the extent to which the suggested price reforms are applied.

e. The agricultural demand for recycled water will be affected

by quality (see below).

f.

The following balances do not include floodwaters. (An

average of 15 MCM/year, according

to current catchment and

reservoir capacities).

Agricultural Consumption (MCM/year)

Sources: (1) and data from

the Consumption Division of the Israel Water Commission (hereinafter: (2) ). See Map No. 3

|

|

|

1998 |

2000 |

2002 |

2005 |

2010 |

|

National System |

Fresh |

774 |

651 |

270 |

470 |

470 |

|

|

Recycled |

269 |

270 |

279 |

339 |

409 |

|

|

Saline |

30 |

30 |

30 |

30 |

30 |

|

|

Total |

1073 |

951 |

579 |

839 |

909 |

|

Peripheral System |

Fresh |

86 |

81 |

82 |

71 |

60 |

|

|

Recycled |

7 |

9 |

16 |

27 |

36 |

|

|

Saline |

160 |

162 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

|

|

Total |

253 |

252 |

258 |

258 |

256 |

|

TOTAL |

Fresh |

860 |

732 |

352 |

541 |

530 |

|

|

Recycled |

276 |

279 |

295 |

366 |

445 |

|

|

Saline |

190 |

192 |

190 |

190 |

190 |

|

|

TOTAL |

1326 |

1203 |

837 |

1097 |

1165 |

Seasonal Distribution: Summer consumption (May – September): 65% of the annual

consumption in a regular year and 60% in a drought year.

Notes:

1. 1998 serves as the representative year for the 1990’s

decade.

2. 1999 to 2001 were drought years with minimal

precipitation.

3. 2002 is an average rainfall year, but the hydrological

crisis is very evident because of the paucity of the aquifer reserves and the

severity of salinity, due to over-pumping during the previous drought years. The

year 1999 (drought year) had a balance similar to that of 1998.

4. In general, the shortage is not only a function of the

precipitation level of a specific year, but mostly, a consequence of the pumping

policy for the aquifers in past years.

Additional Consumption: Water

Allocations for the Environment, Landscape and River Rehabilitation

Freshwater: In the current state of drought and water

scarcity, there is no allocation of water for environmental enhancement and the

natural flow in almost all the rivers is practically nonexistent. This is a

consequence of the extremely low aquifer level.

Recycled wastewater:

·

Currently about 15 MCM/year are utilized for river rehabilitation, 85%

of which are recycled for agricultural irrigation.

·

The government has decided to increase this amount to 40-50

MCM/year, 75% of which will be

restored to the water economy.

Additional Consumption:

According to the peace agreement with

·

35 MCM/year

from the Beit Shean springs.

·

20 MCM/year

restoration of

Note: In years of shortage, taken from the Israeli source

in the

The agreement with the PA calls for:

·

31 MCM/year

from the national system: (Mountain Aquifer).

·

4 MCM/year

from other sources.

Total= 35 MCM/year

·

In addition, the PA pumps 27 MCM/year from the Mountain Aquifer.

Note: We estimate that these quantities will have to be

significantly increased in the future. According to the Master Plan (1), a growth rate of 4.3%/annum is anticipated and

it is reasonable to assume that demand will increase accordingly.

Total net supply to Jordan and the Palestinian Authorities

– 97 MCM/year.

Summary of Water Demand (MCM/year)(1) +

(2)

Summary by Water Type

|

|

|

1998 |

2000 |

2002 (estimate) |

2010 (projected) |

|

National system |

Fresh |

1629 |

1495 |

1106 |

1609 |

|

|

Recycled |

269 |

270 |

279 |

457 |

|

|

Saline |

30 |

30 |

30 |

30 |

|

|

Total |

1928 |

1795 |

1415 |

2095 |

|

Peripheral System |

Fresh |

120 |

113 |

114 |

100 |

|

|

Recycled |

7 |

9 |

16 |

52 |

|

|

Saline |

196 |

199 |

197 |

159 |

|

|

Total |

323 |

321 |

327 |

311 |

|

Total |

Fresh |

1749 (78%) |

1608 (76%) |

1220 (70%) |

1709 (71%) |

|

|

Recycled |

276 (12%) |

279 (13%) |

295 (17%) |

509 (21%) |

|

|

Saline |

226 (10%) |

229 (11%) |

220 (13%) |

189 (8%) |

|

|

TOTAL |

2251(100%) |

2116 (100%) |

1735 (100%) |

2407 (100%) |

Summary of Water Demand by Sector

|

|

1998 |

2000 |

2002 (estimate) |

2010 (projected) |

|

Domestic |

694 31% |

684 32% |

680 39% |

875 36% |

|

Industrial |

129 6% |

132 6% |

131 8% |

167 7% |

|

Agricultural |

1326 59% |

1204 57% |

837 48% |

1165 48% |

|

Environment |

4 - |

2 - |

2 |

40 2% |

|

Jordan & PA |

98 4% |

94 4% |

85 5% |

160 7% |

|

TOTAL |

2251 100% |

2116 100% |

1735 100% |

2407 100% |

Water Supply

Freshwater

There are seven major freshwater basins: six are

underground aquifers and the seventh is the

Salination Levels and Long-Term Average Recharge by Water

Resource (see Map No. 4)

Source: Israeli Geological Service, Hydrological report,

2000

|

Basin |

Salination Level (mgchlorine/liter) |

AverageAnnual-Recharge (MCM) |

|

|

1.Coastal Aquifer |

190-320 |

300 |

|

|

2.Mountain Aquifer |

210 |

360 |

|

|

3. |

180 |

550 |

|

|

4. |

250 |

90 |

|

|

5. |

250 |

40 |

|

|

6. |

320 |

90 |

|

|

7.Eastern Mountains |

150 |

60 |

|

|

TOTAL |

|

1490 |

|

Desalinated Water

Desalinated seawater:

Currently, the desalination plant in Eilat produces 3-5 MCM/year, using water from the

Desalination of saline water (from salinated aquifers and wells): Currently 1-3 MCM/year are being treated, and in the

coming years desalination of an additional 40 MCM/year is planned.

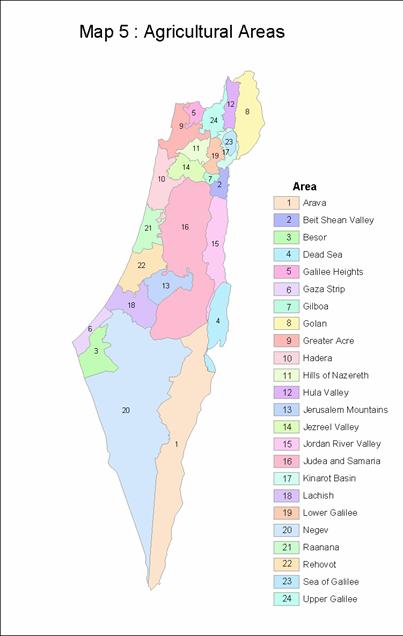

Recycled Water

Following is a list of the main facilities for recycling

wastewater. All of them are partially or wholly owned by Mekorot. (see Map No. 5)

|

Facility |

Water source |

Agri./other consumption

region |

MCM 2002 2010 (est.)(project.) |

Current treatment quality |

Notes | |

|

Shafdan |

Greater Tel-Aviv area |

Western, Northern and |

110 |

140 |

Tertiary + |

Allowed for incidental drinking |

|

|

Greater |

Western Jezreel Valley |

30 |

45 |

Secondary+ |

|

|

|

|

Judean mts., Judean plains & |

15 |

20 |

Tertiary |

|

|

|

Netanya |

Hefer Valley |

8 |

12 |

Tertiary |

|

|

Hadera |

Hadera |

Coastal plain & |

7 |

10 |

Secondary+ |

|

|

TOTAL |

|

|

170 |

227 |

|

|

|

% of total wastewater |

|

|

52% |

45% |

|

|

An additional 25 small and intermediate sized sewage

treatment installations are in operation. Their treatment quality is generally

“Secondary”.

Additional notes: It is estimated that about 100 MCM/year currently flow into the sea.

The possibility of using a large quantity of recycled wastewater for

agricultural purposes is dependent on upgrading it to a quarternary quality level (suitable for all crops),

decreasing the salinity level (desalination of wastewater or the water entering

the city), and pooling the water recycled in the winter for consumption in

summer. Upgraded quality is also needed for river rehabilitation.

General Water Balance (MCM/year)(1) + estimates

The supply and the demand mix are presented for a normal

year selected from the past decade, a year during the current hydrological

crisis, and an average year in the future:

|

|

Normal year (1998) |

Drought year (2002 estimate) |

Future average year

(2010) |

|

Demand by sector: |

|

|

|

|

Domestic |

694 |

680 |

875 |

|

Industrial |

129 |

131 |

167 |

|

Agricultural |

1326 |

837 |

1165 |

|

Jordan & PA |

97 |

86 |

160 |

|

Environment |

5 |

1 |

40 |

|

Total |

2251 |

1735 |

2407 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Demand by water type: |

|

|

|

|

Freshwater |

1749 |

1248 |

1709 |

|

Reclaimed |

276 |

298 |

509 |

|

Saline |

226 |

189 |

189 |

|

Total |

2251 |

1735 |

2407 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Supply: |

|

|

|

|

Aquifers (including saline) |

1975 |

1432 |

1398 |

|

Desalination |

- |

5 |

500 |

|

Recycled |

276 |

298 |

509 |

|

Total |

2251 |

1735 |

2407 |

Water Quality

Water quality is measured according to the following:

·

Salinity – refers to the chlorine level in the

water (indicated by electrical conduction capacity).

·

The presence or absence of chemicals and poisonous

contaminants, especially boron, whose presence has a negative impact on

crops.

·

The level of biological purity (T.S.S., B.O.D.).

The current trend calls for stricter adherence to water

purity standards. An inter-ministerial committee (Inbar Committee) of director-generals recently

issued a report recommending substantially stricter purification standards for

recycled wastewater.

Water quality is multifaceted and has many implications,

including:

a. Water quality for domestic and

industrial consumption – standards and costs.

During shortages it is possible to use high-quality

wastewater for some of these purposes: irrigating public parks, certain

industrial uses, etc. (some households in

When salinity standards are introduced into water

purification standards some towns will have to debate the economic-structural

issue of the “location” for removing salts, i.e., desalination at the “city

gates” or desalination of the wastewater at the “exit”.

b.

Water quality for agricultural

consumption – Factors influencing the possibility of irrigating crops

with wastewater include:

·

Ministry of Health requirements.

·

Salinity level as per the flora-agricultural

requirements.

The salinity level is a function of the water’s salinity

“at the city gates” (entry water), with an added 70-100mg chlorine/liter.

It is important to note that as more desalinated water

becomes part of the

·

The environmental impact of using recycled wastewater,

particularly in sensitive areas above aquifers. Such use must be approved by the

Ministry of the Environment and the Health Ministry.

Also to be taken into account is the environmental impact

of drainage to the rivers in terms of the biological purity level.

Notes:

·

Some salinity problems may be solved by diluting saline

water with fresh or desalinated water.

·

The standards for recycled wastewater at the sewage

treatment facility exit are currently being updated and expanded

(Director-generals Committee, Inbar Committee).

·

Boron – Crops are particularly sensitive to boron. In some

areas the recycled wastewater is rich in boron due to the water entering the

city from wells with high boron concentrations. This is an acute problem,

particularly in the southern Arava and the date plantations there since Eilat’s wastewater is its main water

source. Most of Eilat’s water

comes from desalinated

c.

The interface between water quality

and various environmental issues

A major part of the hydrological crisis is also an

environmental crisis, with continuous pollution of the rivers, aquifers and

other natural resources. Serious ecological damage affecting unique natural

resources and landscapes often result.

·

Technically, treated sewage may be used for agricultural

purposes, diverted to rivers or the sea or a combination of them.

The effect of diverting the treated sewage on the

“receiving” environment and the subsequent environmental demands affect the

technology and the development of water treatments.

Agricultural use of wastewater above an aquifer may

contaminate it, in turn arousing the issue of sustainable water resources and

the problem of creating (or preventing) damage for generations to come.

Dumping in rivers may influence their flora and fauna. Fish

and other animals are extremely sensitive to chlorine.

The Barcelona Accord of the Mediterranean countries

restricts drainage to the sea.

·

The effect on the

The amount of water pumped from the

The crisis of the

d.

Economic Facets of the Issue of

Quality

The demand for a higher level of water quality has clear

economic implications. The debate focuses on who is to carry the financial

burden of upgrading the water treatment plants: the local authorities based on

the principle that the “polluter pays”, the farmers, the consumers or the

government (representing social-environmental interests).

The indecisiveness on these important matters and the

resulting imbalance between sewage supply and treatment, together with

agricultural demands and drainage solutions, are some of the reasons for the

slow transition by farmers to recycled wastewater and is part and parcel of the

overall crisis.

Public regulation and Institutional structure

Description

The following is a partial description of the entities

involved in regulating and allocating resources to the water economy.

The large number of parties involved is most apparent, as

are the implications of the subsequent bureaucratic maze that hinders initiative

and change.

|

Entity |

Regulatory and Implementation

Authority |

|

1. Water Commission (Min. of Infrastructure) (Until

1996-Min. of Agriculture) |

·

Aquifer pumping policy (Operations Comm. of the

Hydrological Service) ·

National & regional planning of installations

(Planning Division), and desalination tenders ·

Allocation of quotas for all water types (Consumption

Division) ·

Encouraging saving water in the various sectors ·

Approval of wastewater reclamation projects ·

Participation in setting water prices ·

Equalization Fund |

|

2. Ministry of Agriculture |

· River drainage and flood prevention (Drainage

Division) · Grant approval for investment in irrigation projects

(Investment Administration) · Right of veto on water prices |

|

3. Ministry of the Environment |

· Initiation and approval of all river administrations’

projects (in conjunction with the Jewish National Fund-KKL) · Authorization for irrigating with recycled wastewater

above aquifers · Authorization to dump wastewater into rivers and the

sea |

|

4. Ministry of Health |

· Purification standards for all water types and all

their uses · Authorization for irrigating

areas adjacent to wells |

|

5. Ministry of the Interior |

· Municipal Water Company

Law · National linear schemes

(TAMA-34) for water and sewage · Setting local authority water

prices (approval by the Min. of Finance) · Approval of district linear

schemes (TAMA) for development of rivers and their environs |

|

6. National Sewage Administration (Min. of

Infrastructure) |

· Approval of sewage treatment

facilities · Allocation of funding to

local authorities for sewage treatment |

|

7. Ministry of Finance (Budget Division) |

· Approval of

Mekorot water prices · Allocation of financial resources (including

subsidies} to the water economy and Mekorot · Initiation of many structural changes in the

framework of the “Arrangements Law” |

|

8. Ministry of Justice |

· Defending the

State in Supreme Court appeals, especially in precedent-setting cases

(numerous cases arise in the water economy) · Approval of

legislation drafts |

|

9. Parliamentary Finance Committee |

· Approval of water

prices (there is a strong agricultural lobby in this forum.) · Approval of

structural changes in the framework of the “Arrangements Law” and the

national budget |

|

10. Parliamentary Economic Committee |

· Established a

sub-committee on the water economy crisis. It is a parliamentary

investigative committee that is to submit recommendations |

|

11. Jewish National Fund (KKL) |

· Provides funding

for reservoirs after having been approved. Implementation usually carried

out by them · Partner in the

River Restoration Administration and in funding |

|

12. Israel Lands Administration (Ministry of

Infrastructure) |

· Allocation of land

for wastewater reservoirs and desalination plants |

Many of these bodies are divided into sub-divisions having

authorization and regulatory powers. Various branches of the same body

frequently do not adhere to a uniform policy.

The Water Supply Institutional Structure

Fresh and saline water:

63% Mekorot

(Government company, operates the national system)

8% Local authorities, private production

29% Private production for agricultural consumption, half

of it by 4 large water cooperatives (

100%

Recycled wastewater and

supply to the agricultural sector

Currently: 67% Mekorot

33% Regional cooperatives

100%

Desalination

Mekorot has rights to 50 MCM

The rest is relegated to

private producers as per the B.O.T. agreement with the government.

Water Pricing and Costs and Capacity building

potential

Water Pricing Policy

·

Water prices are uniform throughout the country, varying

only by sector and quality.

·

Prices are set by the government, based on recommendations

of the Ministry of Finance and the Water Commission, and approved by the

parliamentary finance committee.

·

These prices are for water delivered by the national

company, Mekorot, which operates

the NWC and the Shafdan and supplies some 60% of

freshwater consumption and about 50% of recycled wastewater for agriculture.

·

Private water producers set prices independently, but are

subject to an extraction levy imposed by the government. (This tax is calculated

to reflect the “scarcity price” of water.) Production and distribution of

recycled water in this sector are subject to the approval of the Water

Commission.

·

All water production requires the approval of the Water

Commission (production quotas) as does all water consumption and sale

(consumption quotas). In practice, the latter quotas apply only to the

agricultural sector and are not enforced on domestic and industrial use. (Trade

in quotas is prohibited by law.)

·

Details of water prices are presented below.

Costs

Freshwater in the national system (Mekorot)

Average cost: 0.34 US dollar per m3

Cost structure:

Capital:

40%

Energy:

28%

Work and operation: 32%

Desalination

Cost as per the latest tender for 50 MCM/year in

0.53 US dollar/m3 to the

plant’s gate.

Connection to the national system:

0.07 US dollar/m3

Transport

0.08 US dollar/m3

TOTAL

0.68 US dollar/m3

Treatment of recycled

water

Costs vary greatly according to type and size of the

facility. Larger facilities have cost advantages.

Average costs in US dollars/m3

wastewater

Secondary treatment:

0.39

Upgrade to tertiary:

0.08

Upgrade to wastewater extraction:

0.15

(desalination from 400mg to 50mg chlorine)

TOTAL cost of recycling water for broad agriculture &

ecological use 0.62

Pooling and conveyance of recycled water for agricultural

consumption:

Regional facilities (including land)

0.26 US dollar/m3

Large national facilities (Shafdan)

0.35 US dollar/m3

Consumer Prices of Water in

For consumers linked to

the national system, Mekorot

Local authorities for household use

0.345 US dollar/m3 (at “city gate”)

Industrial

0.330 US dollar/m3 (average)

Agricultural

Agricultural users of freshwater are subject to tiered

pricing and quotas. The farmers pay a reduced price for the first 50% of their

quota, a higher price for the second 30%, and the full price for the rest of the

quota. Separate rates exist for the

Water with over 400mg salinity is charged at a lower rate,

according to its salinity level.

The Shafdan

charges the same rate for summer and winter consumption, but here too there is a

quota.

Recycled wastewater is charged according to a two-tiered

system: the first 50% of the quota at a higher price and the second 50% at a

lower rate.

Agri. Water Rates by

Type Price (December 2001)

In US dollars/m3

Fresh – tier A

0.19

Fresh – tier B

0.23

Fresh – tier C

0.31 (Full use of quota averages 0.23)

Fresh – above quota

0.54

Fresh

0.13

Saline wells

0.07

Springs

0.04

Saline springs

0.014

Saline (average)

0.16

Shafdan – winter

0.15

Shafdan – summer

0.16

Shafdan – above quota

0.54

Other recycled – 1st

50%

0.14

Other recycled – remaining 0.11

User levies on private producers (water not purchased from

Mekorot).

Production (extraction) levies are imposed on all the

producers, including Mekorot, and

are intended to reflect the “shadow price”. They also pay the production and

conveyance costs.

Levies

In US dollar/m3

Coastal Aquifer

0.10

Other aquifers

0.09

Flood and saline

0.00

Water costs for domestic consumers

This is the price to the consumer as charged by the local

authorities. The maximum price is set by the Ministry of the Interior. Pricing

is progressive, based on consumption.

Rate

In US dollar/m3

consumed

Average

1.06

Sewage removal surcharge 0.49

Development plans for the Israeli water economy for the

next ten years

1. Desalination of Mediterranean seawater:

Existing decisions

250 MCM/year

Additional needs

350 MCM/year

TOTAL

600 MCM/year

Investment required: 1.4 billion dollars

2. Desalination of saline water (and saline aquifers):

Amount of water

213 MCM/year (hydrological

research is still required)

Investment required:

320 million dollars

3. Improvement of salinated wells (mainly by the municipal

authorities):

Potential water quantities

80 MCM/year

Investment required:

70 million dollars

4. Wastewater reclamation:

Current amount

280 MCM/year

Planned for end of decade – an additional

230 MCM/year

TOTAL

510 MCM/year

Investment required (estimate): 600 million dollars for

reservoirs and conveyance systems.

Upgrading wastewater for unlimited agricultural and

environmental use, including desalination:

300 MCM/year

5. Additional projects:

Fortification of the supply system along the border 600

million dollars

National filtering systems

50 million dollars

TOTAL

650 million dollars

6. Summary of the Israeli water economy’s needs for the next

ten years (estimate):

Note: Implementation limitations may require extending the

development into the next decade.

Desalination of seawater

1400 million dollars

Desalination of saline water and wells

390 million dollars

Wastewater reclamation

600 million dollars

Upgrading wastewater

600 million dollars

Additional projects

650 million dollars

TOTAL

3640 million dollars

Major Conflicts

·

Competition between the urban and the agricultural sectors

on the limited resources of freshwater. All of the inelastic domestic demand in

the steadily increasing urban sector is covered by freshwater supply, and thus a

large-scale transition in the agricultural water use from good quality water to

reclaimed urban and industrial wastewater is expected.

·

Competition between agricultural and ecological utilization

of recycled wastewater.

·

Competition between farmers in the central and in the

peripheral region of

·

Conflict between the agricultural and the urban sectors on

the purification standards for disposal set for the cities by the government.

Another conflict is on how the costs and the benefits associated with recycling

should be allocated between the generators of sewage (the municipalities) and

the agricultural users. An additional conflict is on how municipalities can be

assured that the farmers will not reduce usage suddenly (due to an economic

crisis for example) and leave the cities with treated water that they cannot

dispose of.

·

New and forthcoming partial privatization of water supply

are a potential source of conflict between the government-owned company, Mekorot, and private entrepreneurs on

two issues: the control of the supply of newly developed water resources (mostly

desalinated sea water and recycled wastewater) and the responsibility for the

operation of the intra-cities water systems (currently operated by the cities

themselves).

·

Conflicts between

Concluding statement

The agricultural sector is the major water consumer and

consequently, most of the changes will affect it. Changes are also needed in

different aspects of urban household consumption, especially due to increased

demand and the introduction of desalination of seawater.

Tel Aviv and the Arava Regions

Tel Aviv Region

Introduction

The region is located in

the coastal plain on the eastern shore of the

Domestic consumption is

similar to the national average (100 ![]() per

capita per annum). This consumption is expected to increase by 20% with the

development of metropolitan parks and the improvement in quality of life. The

quality of the fresh water is good, with a salinity level of 150-250 mg chlorine

per liter. In the future, the use of desalinated water will lead to an

improvement in the water quality. The region’s large population creates the

potential for a large supply of recycled water for agriculture. In addition,

high quality treated waste water can be used for irrigation of metropolitan

parks and for rehabilitation of streams like the

per

capita per annum). This consumption is expected to increase by 20% with the

development of metropolitan parks and the improvement in quality of life. The

quality of the fresh water is good, with a salinity level of 150-250 mg chlorine

per liter. In the future, the use of desalinated water will lead to an

improvement in the water quality. The region’s large population creates the

potential for a large supply of recycled water for agriculture. In addition,

high quality treated waste water can be used for irrigation of metropolitan

parks and for rehabilitation of streams like the

Current and New Paradigms

We start with a bullet-points description of the current

paradigm:

·

There is no private ownership of water in

·

Prices of water delivered by the national company Mekorot are set by the government, and

are determined in a procedure which is open to political pressure (skillfully

applied by the agricultural lobby). Viewing water prices not as an allocation

instrument, but as a means to improve income distribution, water charges depend

on the type of use: farmers pay the lowest prices, industry pays higher prices

and households pay the highest. Within each sector prices do not depend on

location: users in all parts of the country face the same prices, regardless of

the supply price of water. Private water suppliers are subject to quotas but can

set prices independently.

·

The actual planning of water allocation made by the Water

Commission follows several stages:

·

Predicting annual water demand by sector and region

(including, of course, that of Tel-Aviv), given the actual water prices.

o

Determination of "red lines" for each of the major water

sources and the implied total production permits of fresh water;

o

The gap between aggregate demand and total supply of fresh

water is bridged via investments in the water economy aimed at: (i) increasing the volume and

flexibility of the within-region and between-regions conveyance systems of fresh

water, (ii) development of additional (environmentally safe) water treatment

plans, reservoirs and conveyance systems; (ii) improving the quality of fresh

water as well as of the recycled effluents; and, in the longer run, (d)

desalination of sea water.

·

The current management practices result in:

o

Continuous pressure on the governmental budget to increase

the share allocated to investments in the water economy and continuous pressure

of the budget department of the Ministry of Finance to increase water prices,

including the prices for agricultural use.

The above pressure to raise prices is balanced by the

agricultural lobby which is very influential in

These detrimental effects are among the major reasons for

the current severe water crisis. Although still very influential, the

agricultural lobby lost some of its political power in the last two decades.

·

Additional conflict in the water economy exists between the

agricultural and the urban sectors regarding the purification standards for

disposal set for the cities by the government. Another conflict is over the

allocation of the costs and the benefits associated with recycling between the

generators of sewage (the municipalities) and the agricultural users. An

additional conflict is the issue of assurance for the municipalities that the

farmers will not reduce usage suddenly (due to an economic crisis for example)

and leave the cities with treated water that cannot be disposed of.

·

New and forthcoming partial privatization of water supply

is a potential source of conflict between the government-owned company, Mekorot, and private entrepreneurs on

two issues: the control of the supply of newly developed water resources (mostly

desalinated sea water and recycled wastewater) and the responsibility for the

operation of the intra-cities water systems (currently operated by the cities

themselves).

The current paradigm is the result of inefficient

institutional and administrative mechanisms for water allocation and of a poor

decision making culture (hydro-politics). The above-mentioned unsolved ongoing

conflicts partially paralyze the water economy. This is especially true in a run

of dry years (as in 1998-2001) in which many of the problems become more severe.

The main quantitative expression of the current crisis is the severe reduction

in the ability to produce freshwater from the aquifers (approximately 500MCM)

without operating additional wastewater reclamation systems and desalination

plants. The agricultural sector bears the brunt of the cuts (since the demand of

the other sectors is rigid), and its allocation was recently reduced by about

40%.

To conclude:

New Paradigm for Tel-Aviv Region

Intensifying the reclamation of wastewater for agricultural

purposes and for river rehabilitation. A large

scale transition in agricultural water use from good quality water to reclaimed

urban and industrial waste water is expected in the forthcoming years. This

shift requires the development of many more environmentally safe water treatment

plants, reservoirs and conveyance systems. The urban water economy from the

city gate to the consumers, to the treatment plant and to final disposition is

becoming as big as the economy of fresh water and it is growing

steadily. The

current trend calls for stricter adherence to water purity standards. An

inter-ministerial committee of director-generals recently issued a report

recommending substantially stricter purification standards for recycled

wastewater in the near future.

Cost-benefit analysis of the above-mentioned large-scale

transition should take into consideration:

·

The spatial distribution of aquifers and the environmental

costs associated with irrigation above them, which may pollute the underlying

groundwater.

·

The question of how the costs and the benefits associated

with recycling should be allocated between the generators of sewage (the

municipalities) and the agricultural and ecological users.

·

The question of how municipalities can be assured that the

farmers will not reduce usage suddenly (due to an economic crisis for example)

and leave the cities with treated water that they cannot dispose of.

·

At the farm level one should investigate farmers'

incentives to adapt crop varieties to water of lower quality and evaluate the

negative environmental externalities associated with sustained use of treated

wastewater.

Reform in

Water Allocation Practices - - Allocation by Prices

The goals of a reform in water pricing are to increase the

overall efficiency of water allocation to the agricultural sector, by raising

water prices to an "economically efficient" level, and at the same time to give

farmers incentives, via adequate land-dependent cultivation subsidies, to strive

towards the national goal of protecting the land and preserving the

landscape. The

efficient prices should reflect the long run costs of water supply, including

the scarcity value of water, and the environmental costs associated with water

production and/or water use. More specifically, the analysis of the reform in

water pricing should cope with the following questions:

·

How should prices vary by water quality? The quality

requirements for urban consumption are much higher than the requirements for

agricultural use, but water in Tel Aviv's region is supplied via the same

national conveyance system. Should the prices for the agricultural and the urban

sectors be identical? Should farmers pay the extra costs required to meet the

standards of urban use?

·

How should prices vary by reliability of water supply? The

supply to the urban and industrial sectors in

·

How should the spatial variation of water prices reflect

the spatially variable extraction and transportation costs? If equity

considerations imply an homogeneous price for water of a given quality, one

should evaluate the "efficiency cost" of the equity requirement. It should be

noted that an homogeneous price implies cross-subsidization among users in

different regions.

·

In addition to sending signals to water users about the

full cost of water supply, prices should also cover the costs of supply. In the

case that total revenues collected by the suppliers exceed (fall short of) the

total costs of supply, rebate to users (governmental subsidy to water producers)

should be considered.

A massive

desalination of seawater is another important action that will be taken in

The Arava

Region

Introduction

The region is located at

the south-eastern tip of

The water supply system

in the Arava is not part of the national water system. The region

receives water from local sources only, via the national water company Mekorot. Drillings in the

center of the region (Faran

drillings) yield water of reasonable quality - up to 350 mg chlorine per liter.

Drillings in the southern Arava

yield low-quality water of 600-1,100 mg chlorine per liter. It is important to

note that the Red Sea is a unique coral reserve of great ecological value, and

it is therefore essential that waste water be recycled for agriculture and not

be disposed of in the sea.

Current and New Paradigms

We start with a bullet-points description of the current

paradigm:

·

The prices for all the water supplied by Mekorot, fresh and saline, are determined within the

national framework. Saline water is cheaper than fresh water, in accordance with

the salinity level. The price for recycled water for agriculture covers the

operational and the capital costs of Mekorot, after discounting state grants.

·

The desalination plant of

·

The utilization of recycled waste water produced in Eilat for irrigation is insufficient

and inefficient, due to lack of adequate storage facilities and conveyance

systems as well as poor institutional structure. The potential to recycle

wastewater produced in the rural villages is not utilized as well.

New Paradigm for the Arava Region

The general principle is

to introduce regional administration of the water sector, with institutional and

economic separation of the Arava

water resources from the national water system. The water development plans for

the region are mainly for pooling and transferring waste water.

The details of this principle are threefold:

·

All water supplied to the city of

·

Wastewater “produced” by the city of

·

Water prices for agriculture will be determined

independently of the national system so as to reflect the specific cost of their

production. Prices of recycled wastewater will be determined by negotiation

between the city of

It should be noted that

the Arava region borders with

A Brief Summary of Relevant Data for the Selected Regions

Some of the relevant data required for our analysis are

summarized in the tables below. The data in all tables refer to the year 2000.

Population

Distribution of population by type of settlement

|

Type of Settlement |

Tel - Aviv |

Arava | ||

|

|

thousands |

% |

thousands |

% |

|

Metropolitan areas (Pop. exceeding 200,000) |

359 |

18 |

- |

0 |

|

Big cities (Pop. 100,000-200,000) |

902 |

47 |

- |

0 |

|

Mid-sized cities (Pop. 20,000-100,000) |

485 |

25 |

41 |

87 |

|

Small towns and cities (Pop. 2,000-20,000) |

149 |

8 |

- |

0 |

|

Villages and communities |

42 |

2 |

5 |

13 |

|

TOTAL |

1,937 |

100 |

46 |

100 |

The Arava region is sparsely populated, based mainly on the

tourist city of

Domestic, Industrial, Agricultural

and Environmental Water Consumption

Domestic Consumption (MCM/year)

|

Year |

m3 / capita |

Consumption from National System |

Consumption from Local System |

Total Demand |

|

Tel - Aviv |

100 |

75 |

119 |

194 |

|

Arava |

200 |

0 |

9 |

9 |

Industrial Consumption (MCM/year)

|

Year |

Freshwater |

Saline Water |

Recycled Water |

Total | ||

|

|

Consumption from National System |

Consumption from Local System |

Total Demand |

|

|

|

|

Tel - Aviv |

23 |

35 |

58 |

0 |

0 |

58 |

|

Arava |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

Agricultural Consumption (MCM/year) Sources:

|

|

|

Tel - Aviv |

Arava |

|

National System |

Fresh |

33 |

- |

|

|

Recycled |

5 |

- |

|

|

Saline |

- |

- |

|

|

Total |

38 |

- |

|

Local System |

Fresh |

51 |

15 |

|

|

Recycled |

- |

5 |

|

|

Saline |

- |

14 |

|

|

Total |

51 |

34 |

|

TOTAL |

Fresh |

84 |

15 |

|

|

Recycled |

5 |

5 |

|

|

Saline |

- |

14 |

|

|

TOTAL |

89 |

34 |

Environmental Consumption (MCM/year) Sources:

|

|

|

Tel - Aviv |

Arava |

|

Local System |

Fresh |

- |

- |

|

|

Recycled |

2 |

- |

|

|

Saline |

- |

- |

|

|

Total |

2 |

- |

The Tel-Aviv region is

characterized by relatively high domestic and industrial consumption, and

relatively low agricultural consumption. The opposite is true with respect to

the Arava Region. The large

population of Tel-Aviv region creates the potential for a large supply of

recycled water for agriculture. In addition, high quality treated waste water

can be used for irrigation of metropolitan parks and for rehabilitation of

streams like the

Water Supply and General water Balances; Salinity Level of

Water Resources

General Water Balance (MCM/year)

|

|

Tel - Aviv |

Arava |

|

Demand by sector: |

|

|

|

Domestic |

188 |

9 |

|

Industrial |

58 |

1 |

|

Agricultural |

90 |

34 |

|

Jordan & PA |

- |

- |

|

Environment |

2 |

- |

|

Total |

338 |

44 |

|

|

|

|

|

Demand by water type: |

|

|

|

Freshwater |

331 |

25 |

|

Reclaimed |

7 |

5 |

|

Saline |

- |

14 |

|

Total |

338 |

44 |

|

|

|

|

|

Supply: |

|

|

|

Aquifers (including saline) |

333 |

30 |

|

Desalination |

- |

9 |

|

Recycled |

5 |

5 |

|

Total |

338 |

44 |

Salinity Levels and Long-Term Average Recharge by Water

Resource

|

Basin |

Salinity Level (mgchlorine/liter) |

Average Annual-Recharge (MCM) |

|

Coastal Aquifer – National System and Local

Producers |

- |

250 |

|

|

- |

180 |

|

Arava – Local Sources |

400 |

- |

|

TOTAL |

400 |

214 |

Natural water

sources in the Tel-Aviv region are:

1.

Supply from the national water system (via the national

water network of the Mekorot

company):

a.

Production from the coastal aquifer, above which the region

lies

b.

Water supply from the

2.

In addition, part of the fresh-water is provided by private

producers from the coastal aquifer (some 35% of the fresh water).

3.

In the future, this region is slated to receive a

significant amount of the desalinated sea water. Domestic consumption is similar

to the national average (100 m3 per capita per annum). This consumption is

expected to increase by 20% with the development of metropolitan parks and the

improvement in quality of life.

The quality of the fresh

water is good, with a salinity level of 150-250 mg chlorine per liter. In the

future, the use of desalinated water will lead to an improvement in the water

quality.

The Arava is not part of the national water system, but

receives water from local sources only, via the national water company Mekorot:

Drillings in the center

of the region (Faran drillings)

yield water of reasonable quality: up to 350 mg chlorine per liter.

Drillings in the

southern Arava yield low-quality

water: 600-1,100 mg chlorine per liter. The desalination plant of

In addition, waste water

for agriculture is obtained from Eilat and the agricultural settlements. It is

important to note that the Red Sea is a unique coral reserve of great ecological

value, and it is therefore essential that waste water be recycled for

agriculture and not be disposed of in the sea.

The water development

plans for the region are mainly in the area of pooling and transferring waste

water. In the more distant future there is a possibility that the desalination

plant in Eilat will be

enlarged.

Summary Matrix and Map

This section is summarized via a detailed summary matrix

and a map in which the borders of the two selected regions are outlined.

Summary Matrix of Israeli Regions

|

|

|

|

Tel

- Aviv |

Arava |

|

Natural conditions and infrastructure |

Regional Context |

Climate Type |

Semiarid |

Hyperarid |

|

Aridity Index |

0.05-0.2 |

0.5-0.65 | ||

|

Permanent Population |

1,937,000 |

46,200 | ||

|

Water availability |

Total Water Resources / Availability (MCM) |

343 |

44 | |

|

Trans-boundary water |

|

| ||

|

Water quality |

Quality of surface water |

- |

- | |

|

Quality of groundwater |

Good |

Poor | ||

|

Quality of coastal water |

- |

- | ||

|

Water Supply |

Percentage of supply coming from: v Groundwater v Surface water v Desalination v Recycling v Importing |

99% 0% 0% 1% 0% |

68% 0% 21% 11% 0% | |

|

Network coverage: v Domestic v Irrigation v Sewerage |

100% 100% 100% |

100% 100% 100% | ||

|

Economic and Social System |

Water use |

Water consumption by category: v Domestic v Irrigation v Industrial and energy production |

56% 17% 27% |

21% 77% 2% |

|

Population to resources index |

|

| ||

|

Water demand |

Water Demand trends v Domestic v Industrial v Agriculture v Rivers |

Steadily increasing Steadily increasing Transfer to recycled

water Use of recycled

water |

Stable Stable Transfer to recycled

water - | |

|

Consumption index |

Stable per-capita urban consumption |

Stable per-capita urban consumption | ||

|

Exploitation index |

100% |

100% | ||

|

Pricing system |

Average household budget for domestic water (pa)

|

$100 |

$130 | |

|

Average household budget for agricultural water

|

|

| ||

|

Average household income |

|

| ||

|

Cost recovery |

|

| ||

|

Price elasticity |

Agricultural demand is somewhat elastic. Elasticity

of urban and industrial demands are small. |

Agricultural demand is somewhat elastic. Elasticity

of urban and industrial demands are small. | ||

|

Social capacity building |

Public participation in decisions |

Very High |

Very High | |

|

Public education on water conservation

issues |

Fair |

Fair | ||

|

Decision Making Process |

Water Resources Management |

Water ownership |

State |

State |

|

Decision making level (municipal, regional, national)

regarding: v Water supply for each sector v Water resources allocation for each sector |

National National National |

National Local Local | ||

|

Water Policy |

Local economy basis |

National |

National | |

Development priorities |

Recycling and Desalination |

Recycling and Desalination |